Arqueoastronomía preincaica en la costa central del Perú: El Templo del Zorro y el Observatorio de las 13 Torres de Chankillo.

Astronomical science on the central coast of Peru was vital in the agricultural revolution and cultural leap to the Neolithic: The Temple of the Fox and the Observatory of the 13 Towers of Chankillo are two milestones of stargazing uninterrupted for thousands of years : evidence that the central coast of Peru was one focus of the Archaeoastronomy of the Andes and the Americas. Undoubtedly there are other ancient astronomical observatories to be discovered.

La ciencia astronomica en la costa central del Perú fue fundamental para concretar la revolución agrícola y dar el salto cultural al neolítico: El Templo del Zorro y el Observatorio de las 13 Torres de Chankillo son dos hitos de observación de los astros ininterrumpida por miles de años: evidencian que la costa central del Perú fue uno de los focos de la arqueoastronomía en los Andes y en Las Américas. Indudablemente hay otros antiguos observatorios astronómicos aún por descubrir.

El observatorio astronómico mas antiguo de América, con una antiguedad de 4,200 años según fechado radiocarbónico, fue contruido por los antiguos pobladores del valle del río Canta en el departamento de Lima, Perú. En el mes de mayo de 2006, el arqueólogo Robert Benfer de la Universidad de Missouri en Columbia, anunció el descubrimiento del observatorio astronómico mas antiguo de América. El Templo del Zorro, localizado en el valle del río Chillón en Perú, probablemente sirvió de almanaque para los agricultores, acontecimientos anuales importantes fueron determinados por el movimiento del sol y las estrellas, indicó Benfer.

Las pruebas del radiocarbono lo han fechado cercano al año 2200 a.C., unos 800 años antes de la fecha calculada en estimaciones previas para las primeras estructuras que rastreaban estrellas en Sudamérica.

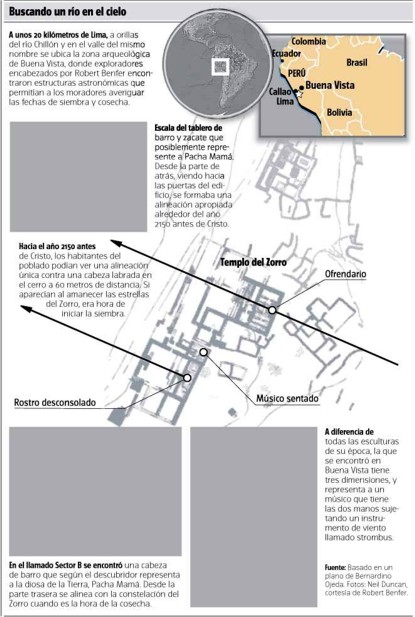

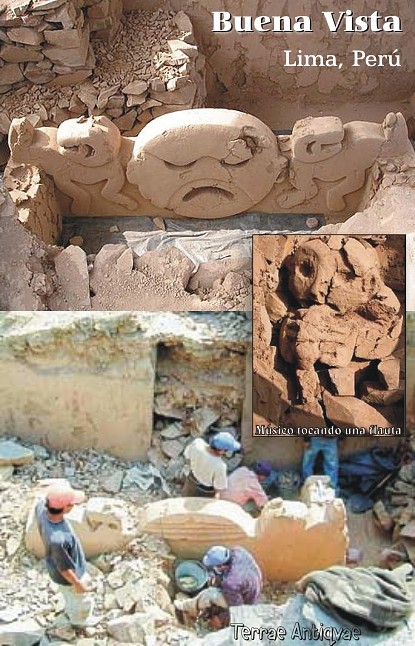

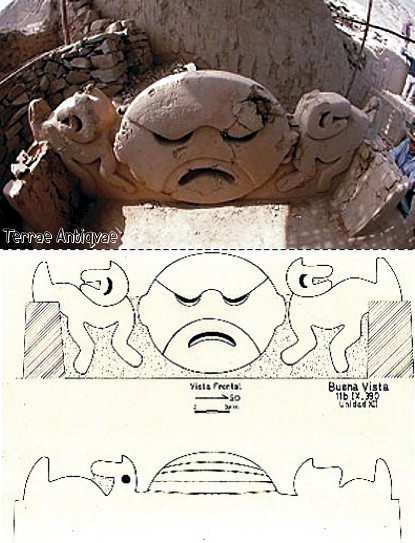

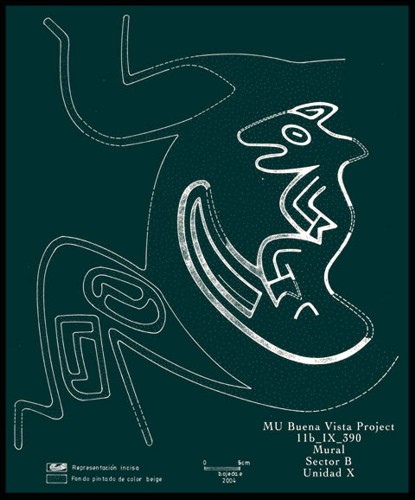

Benfer le puso THE TEMPLE OF THE FOX después de revelar el mural de un zorro, un animal que la mitología andina relacionaba con la agricultura. El sitio también ha permitido descubrir la momia de una mujer, la escultura de un hombre tocando una trompeta, y una enorme cara de ceño fruncido hecha de barro. El cuarto de ofrendas del templo mira hacia una gigantesca roca redondeada ubicada a varios cientos de metros, la cual habría sido tallada en forma de cabeza humana. Dos piedras señalan la salida del sol durante el solsticio de verano en el hemisferio sur, el caudal del río Chillón aumenta alrededor de esa fecha, señalando así el principio de la estación creciente. El 21 de marzo, cuando se reduce el caudal, las dos piedras señalan a la constelación andina del zorro, la cual se asociaba a la lluvia y a la agricultura.

//

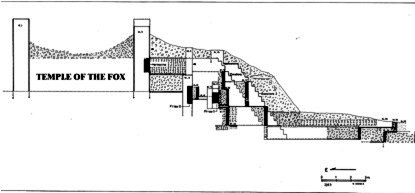

Templo del Zorro. La Pirámide de Buena Vista cercana a Lima (Perú) es un observatorio celeste de 4200 años de antigüedad

terraeantiqvae.blogia.com/temas/america.php

Fotos: (1) GATEWAY: Archeologist Robert Benfer’s team found this clay sculpture of a frowning face at the Buena Vista site near Lima. The disk, marks the position of the Southern Hemisphere’s winter solstice. (Robert Benfer / University of Missouri)(2) MUSICIAN: The team found this sculpture of a figure playing a pipe at the Buena Vista site, the oldest found in the region. (Robert Benfer / University of Missouri)

¿Pirámide andina era un almanaque agrícola?

Se construyó para avisar a los sacerdotes que ya era la hora de la siembra o la cosecha. El complejo, en las cercanías de Lima, se edificó hace 4,200 años. terraeantiqvae.blogia.com/temas/america.php

Robert Benfer, antropólogo de 67 años, encontró en la ladera de una colina, a unos kilómetros de la capital peruana, lo que en su opinión es el calendario más antiguo del Nuevo Mundo: un observatorio de cuatro mil 200 años de edad, construido con suficiente precisión para fungir como almanaque agrícola.

“Estaba mirando una escultura situada en una cresta encima del templo y me di cuenta de que todo se alineaba con las estrellas. Fue un momento sorprendente”, dijo.

“La alineación significaba que al amanecer de cada solsticio de invierno, hace cuatro mil 200 años, estrellas clave aparecían alineadas con el templo, y alertaban a los sacerdotes que pronto el río se anegaría y sería tiempo de empezar a sembrar. (El templo) había sido edificado como un despertador para la comunidad”.

Benfer sacó del olvido una pirámide construida en el año 2200 antes de Cristo, evidencia de que los antiguos pueblos andinos conocían los movimientos de las estrellas en fecha tan remota que ni siquiera los bretones antiguos habían terminado de construir Stonehenge.

Benfer exploraba el Valle del Río Chillón en busca de informes acerca de dietas precolombinas, y se tropezó con una pirámide de casi diez metros de alto que en sus días estuvo pintada de blanco y rojo.

El sitio, ubicado en el enclave arqueológico de Buena Vista, está dominado por dos edificios: la pirámide del norte, el Templo del Zorro, se construyó alrededor de una plataforma desde la cual los sacerdotes ofrendaban a los dioses.

A través de puertas angostas, el ofertorio miraba hacia una piedra labrada en forma de cabeza. La roca, de casi 2.5 metros de alto, está en la cresta de una montaña a unos 60 metros de distancia. Cada año, al llegar el solsticio de verano del hemisferio sur, el día más largo del año (21 de diciembre), una constelación que para aquel pueblo era el Zorro aparecía alineada con la piedra. Esto ocurría unos días antes de que el río Chillón, del que dependía su agricultura, se inundara.

Los mitos andinos dicen que el Zorro enseñó a los lugareños las artes de la agricultura.

Más al sur, otra de las estructuras tiene una tableta de barro y zacate que luce en su centro un redondo rostro de ceño fruncido. Benfer cree que la tableta representa a Pacha Mamá, la diosa de la Tierra. Mirando desde atrás de la estructura y a través de las puertas, los sacerdotes podían ver aparecer estrellas justo cuando debía recolectarse la cosecha anual.

Larry Adkins, profesor de astronomía en el Colegio Cerritos, de California, dijo que las alineaciones eran más que una conincidencia. “Tal vez no sean precisos para los estándares modernos, pero se acercan lo bastante para permitir a los sacerdotes (de la época) producir muchas predicciones”.

En medio del ofertorio y la tableta los arqueólogos hallaron también una escultura que representa a un músico tocando lo que parece ser una concha.

Lo más peculiar de la figura, cuyas piernas aparecen colgando de un balcón, es que su torso es redondo: es una verdadera figura tridimensional, insólita en un tiempo en que sólo había altorrelieves de dos dimensiones.

terraeantiqvae.blogia.com/temas/america.php

Fuente: Milenio.com, México, 23 de mayo de 2006

Enlace: http://www.milenio.com/mexico/milenio/nota.asp?id=86949

(2) El Templo del Zorro. El disco del ceño fruncido fue descubierto en Perú en Junio de 2005. (HANDOUT)

Por Kavita Kumar y Emily Dulcan

ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH

Ayudó a relacionar un cráneo con los restos del explorador español Francisco Pizarro. Y llevó al equipo que excavó el pueblo más viejo conocido en América.

Robert Benfer, ahora jubilado profesor de antropología de Columbia University en Missouri, trabajando con un equipo de arqueólogos, tiene otro excitante hallazgo para añadir a su impresionante currículum: descubrir un antiguo templo que dice contener la escultura y las estructuras astronómicamente orientadas más antiguas encontradas en el Nuevo Mundo.

Benfer y su equipo descubrieron el templo pirámide de los 33 peldaños, el Templo del Zorro, en un sitio de excavación de 20 acres en Buena Vista, Perú. Dice que el templo se remonta a 2220 a.C. – lo cual lo hace 1,000 años más viejo que cualquiera de su clase antes encontrado, dijo.

La vinculación del templo con el sol y las constelaciones con el equinoccio y el solsticio de verano e invierno indica que los andinos tempranos usaron señales astronómicas y constelaciones para controlar sus actividades agrícolas.

"Es un hallazgo grande - encontrando algo nuevo y sin precedente", dijo Benfer. “Es como si los matemáticos encontrando una nueva interrogante.”

Benfer, 67, presentó al equipo de su hallazgo la noche del lunes en Mizzou como el último de una serie de expositores patrocinados por el Archaeological Institute of America. Está planeando volar hoy a Puerto Rico donde presentará sus conclusiones a la Society for American Archaeology.

Scott de Brestian, presidente de la central Missouri chapter of the Archeological Institute of America, dijo que el descubrimiento de Benfer del templo construido con precisión quiere decir que los calendarios humanos sofisticados existían más tempranamente de los que antes se pensaba.

“Esto realmente cambia nuestra visión de cómo fueron realmente algunas de estas tradiciones culturales", dijo de Brestian.

El trabajo de Benfer "empuja hacia atrás la atención andina a la astronomía en la civilización temprana a más de 4,000 años atrás", dijo Michael Moseley, un antropólogo de University of Florida que ha trabajado en Perú durante más de 30 años. “Esto es pionero”.

Moseley agregó que el descubrimiento de Benfer alienta al resto de su campo a poner más atención a la astronomía en sus trabajos.

Benfer puntualiza que no encontró el sitio solo. Estadounidenses que toman el crédito por descubrimientos arqueológicos en Perú han resultado en controversias en el pasado.

Benfer trabajó con un equipo de arqueólogos peruanos, incluyendo a Bernardino Ojeda, y estudiantes de universidades peruanas y de la University of Missouri.

Los vínculos astronómicos que Benfer y su equipo encontraron marcan fechas importantes para el cultivo. Lo cual sugiere que las civilizaciones tempranas en Perú dependían de la agricultura más fuertemente de lo que hemos creído.

Benfer sabe que otros científicos podrían recibir sus conclusiones con el escepticismo - y deben. Pero piensa que tiene un caso convincente porque encontró múltiples alineamientos "Y ésos no van a ocurrir por casualidad", dijo.

La orientación física de la cámara de las ofrendas es ligeramente diferente del resto del templo, así que está directamente alineado con el sol naciente del 21 de Diciembre, la fecha del solsticio de verano del Hemisferio Sur. Que es cuando crece el caudal del cercano río Chillón y deben haber sido plantados los cultivos. Mirando al oeste, la cámara se alinea directamente con una plataforma natural sobre la que el sol se pone el 21 de Junio, señalar el comienzo de la cosecha.

En el mismo punto sobre el oeste, personas que vivían hace 4,000 años habrían observado el ascenso de la constelación de la estrella del Zorro el 21 de marzo, cuando bajo el caudal del agua.

La relación del templo con el sol ha permanecido casi exactamente el mismo con el paso de los milenios, mientras que las constelaciones han cambiado, y la relación del templo con la constelación de Zorro no es más la misma, dijo Benfer.

El Templo del Zorro es nombrado por el grabado de un zorro encontrado en la entrada del templo. En las culturas andinas, el zorro se relacionado con el agua.

Una de dos esculturas en el templo es una cara flanqueada por dos animales.

Benfer califica la cara como "desconsolada". Está exactamente orientada como la cámara de las ofrendas. Benfer especula que la cara podría ser una de las caracterizaciones más tempranas de la Pacha Mama, el dios o la diosa andina o la diosa que los creyentes pensaron creadora de la tierra.

Casi nunca llueve en Buena Vista, dijo Benfer, así que las restos encontrados en el sitio de excavación estaban en bastante buenas condiciones. Encontraron ramitas y pedazos de algodón que dataron por radiocarbono y resultaron tener 4,000 años, dijo.

Benfer empezó a enseñar en el University of Missouri en 1969. Se jubiló en el 2003 pero continúa trabajando con estudiantes graduados.

Ha estado trabajando en Perú desde los 1970s, viajando allí casi todos los años - a veces más de una vez. Ha estado trabajando en el sitio de Buena Vista durante cuatro años descubrió el templo del Zorro en Junio de 2004.

Espera regresar para regresar al Perú este verano para continuar la excavaciones en el sitio.

Fuente: C/. Louis hoy, 24 de abril de 2006

Enlace: http://www.stltoday.com/stltoday/news/stories.nsf/

education/story/62FEB7BBE05643158625715B00209429?OpenDocument

Traducción: V.F.H. Abril de 2006

Celestial Find at Ancient Andes Site

The discovery in Peru of a 4,200-year-old temple and observatory pushes back estimates of the rise of an advanced culture in the Americas.

Archeologists working high in the Peruvian Andes have discovered the oldest known celestial observatory in the Americas — a 4,200-year-old structure marking the summer and winter solstices that is as old as the stone pillars of Stonehenge.

The observatory was built on the top of a 33-foot-tall pyramid with precise alignments and sightlines that provide an astronomical calendar for agriculture, archeologist Robert Benfer of the University of Missouri said.

The people who built the observatory — three millenniums before the emergence of the Incas — are a mystery, but they achieved a level of art and science that archeologists say they did not know existed in the region until at least 800 years later.

Among the most impressive finds was a massive clay sculpture — an ancient version of the modern frowning "sad face" icon flanked by two animals. The disk, protected from looters beneath thousands of years of dirt and debris, marked the position of the winter solstice.

"It’s really quite a shock to everyone … to see sculptures of that sophistication coming out of a building of that time period," said archeologist Richard L. Burger of Yale University’s Peabody Museum of Natural History, who was not involved in the discovery.

The find adds strong evidence to support the recent idea that a sophisticated civilization developed in South America in the pre-ceramic era, before the development of fired pottery sometime after 1500 BC.

Benfer’s discovery "pushes the envelope of civilization farther south and inland from the coast, and adds the important dimension of astronomy to these ancient folks’ way of life," said archeologist Michael Moseley of the University of Florida, a noted Peru expert.

The 20-acre site, called Buena Vista, is about 25 miles inland in the Rio Chillon Valley, just north of Lima. "It is on a totally barren, rock-covered hill looking down on a beautiful fertile valley," said Benfer, who presented the find last month in Puerto Rico at a meeting of the Society for American Archeology.

The site is remarkably well preserved, Benfer said, because it rains in the area only about once a year.

The name of the people who inhabited the region is unknown because writing did not emerge in the Americas for 2,000 more years. Some archeologists call them followers of the Kotosh religious tradition. Others call them late pre-ceramic cultures of the central coast. For brevity, most simply call them Andeans.

Benfer and archeologist Bernardino Ojeda of Peru’s National Agrarian University have been working at Buena Vista for four years. The site contains ruins dating from 10,000 years ago to well into the ceramic era in the first millennium BC.

The large pyramid and a temple occupy about 2 acres near the center of the site. Radiocarbon dating of cotton and burned twigs found in the temple’s offering pit place its use at about 2200 BC.

That is about 400 years after the first pyramid was built in Egypt and about the same time that the peoples who would become the Greeks were settling into the Mediterranean region.

The temple is built of rock that was covered with plaster and painted, although most of the white and red paint has long since flaked off.

Benfer calls it the Temple of the Fox because a drawing of a fox is carved inside a painted picture of another animal, probably a llama, beside each doorway. According to Andean myth, the fox taught people how to cultivate and irrigate plants.

As the team mapped out the site, Benfer observed that a person standing in the doorway of the temple and gazing through a small, flap-covered window behind the altar is aligned with a small head carved onto a notch of a distant hill. The line had an orientation of 114 degrees from true north, pointing southeast.

Benfer does not normally deal with archeoastronomy — the science of ancient astronomy — so he contacted a childhood friend, Larry Adkins of Tustin, and asked him what that angle signified.

Adkins, a physicist who is retired from Rockwell International and who now teaches astronomy at Cerritos College, told him 114 degrees pointed the way to sunrise on the Southern Hemisphere’s summer solstice, Dec. 21, the longest day of the year.

"That really got the ball rolling," Adkins said.

The summer solstice marks planting time, as the Rio Chillon begins its annual flooding, fed by melting ice higher up in the Andes. The flooding deposits fresh soil on the land, fertilizing the crops and eliminating the need for manure from domestic animals.

Fuente: Thomas H. Maugh II / Los Angeles Times, 14 de mayo de 2006

Enlace: http://www.latimes.com/news/nationworld/world/la-sci-

observatory14may14,0,3343915.story?coll=la-home-headlines

*******************************

White painted and incised mural on the interior wall of the main temple’s entry.

A tracing of the mural on the left by Bernardino Ojeda. The image appears to be an animal inside the body of another animal.

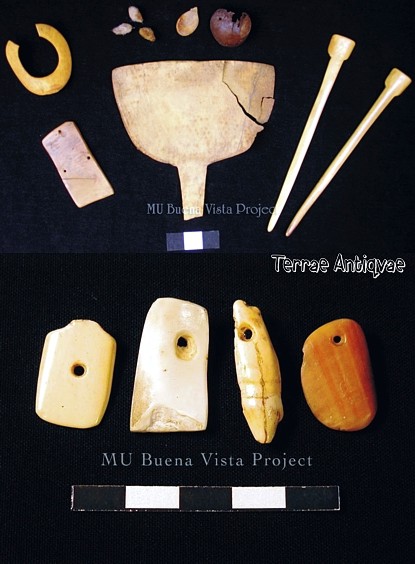

(1) A selection of items recovered from the contents of the sunken pit in the main temple room.(2) Three pendants made from shell and one of a tooth found in the early component of the site.

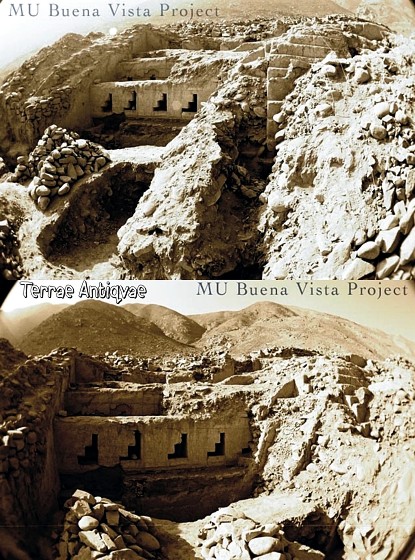

(1) Partially excavated temple mound. Facing West. The stair-shaped niches in the first wall were exposed by archaeologists decades ago. (2) Another view of the temple mound.

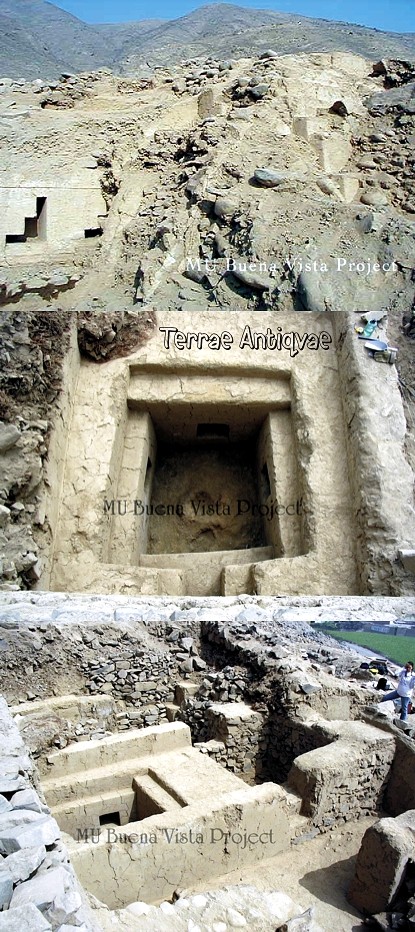

(1) A veiw of the temple mound facing the Southeast. Notice the remains of later architecture and the large stairway to the top. (2) A birdseye view of the sunken pit. (3) Facing South, the main room of the temple partially excavated. The entire room was not excavated.

PHOTOS © 2004 Neil Duncan (Missouri University; Buena Vista Project)

---------------------------------

Detail of one of the animal attendants to the moon disk. Photo credit: Neil A. Duncan, 2005.

Detail of the bust of person playing a conch shell trumpet. Photo credit: Neil A. Duncan, 2005

Buena Vista

Archaeology at Buena Vista was supported by a University of Missouri Research Board grant to Robert Benfer, and by MU Summer Archaeology Field Schools in 2003 and 2004. The Principle Investigator is Bob Benfer. Field crews were directed by Neil Duncan and Bernardino Ojeda.

Buena Vista is located approximately 40 km inland from the Pacific Ocean in the Chillon Valley just north of Lima, Peru. The site was known as “Los Frisos.” The Frisos are, in fact, geometric niches found at the site that are unique in the area.

Archaeologist Frederic Engel identified the site as Preceramic, dating to the time period in Peru before ceramics came into use, and a single radiocarbon date from grass fibers used in the plaster on one of the walls yielded a date of around 3713 BP. However, later surveys of the area identified the site as Late Intermediate period. The site has at least two distinct architectural styles that may have led to the misidentification of the Preceramic component and there are late ceramics on the surface of the site. However, the later architectural components differ significantly in spatial orientation and construction. Unworked-stone walls lacking plaster or mortar predominate in the later area. The older component consists of multiple rooms in adjoining structures of plastered stone walls. In this area we located the main ceremonial feature of the site.

Archaeological testing, including mapping, was conducted in 2002 in both the late and Preceramic areas of the site. A radiocarbon date from a hearth in the later occupation of the site places this component in the time period known as Early Intermediate, the time of the Lima "State". Also, the test excavations confirmed the site’s antiquity, by revealing extensive buried architecture below that which is visible on the surface in the older part of the site. The complexity of the architecture here became apparent. The earliest construction was filled in with loose rock atop which a room and floor layered with plaster was built. Sometime later, the stairwell was filled in. A calibrated C14 date from a refuse feature found in the unit and a calibrated date from charcoal dated by AMS found on the landing of the stairwell dated, 3660 calBP and 3468 calBP, respectively. A small hearth feature was also uncovered. It contained shellfish remains and seeds of Lageneria and Cucurbita. Ceramics were not found in this context.

Other test pits found evidence of shicra, or braided cane bags filled with stone to serve as the foundation. This technique was also used in the Preceramic construction at El Paraiso (Quilter 1991) and other monumental sites of the time.

The first season at Buena Vista confirmed the site’s transitional Preceramic/Initial Period component and an adjacent Early Intermediate component, although more data is needed to firmly establish the latter’s chronological and cultural affinity. For the earlier component, paleoethnobotanical and bioarchaeological, and artifact analyses are underway to answer some of our research questions and undoubtedly these investigations will raise more questions than answers.

We wish to acknowledge the support of the MU Research Board, the Instituto Nacional de Cultura de Peru for granting permission to excavate at Buena Vista in 2002, 2003, and 2004, Field School Co-Director Dr. Hugo Ludeña of the Frederico Villareal University of Lima, archaeologist Bernardino Ojeda R. for his expertise and knowledge, Dra. Miriam Viajos of the Museo de Arqueologia, C.I.Z.A for the use of lab space and curation, and all of the students of the MU Summer Archaeology Field Schools.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Chankillo. Unas torres de piedra forman el observatorio más antiguo en Perú

La construcción revela que el conocimiento de la astronomía existía en la región desde antes del Imperio Inca. REUTERS terraeantiqvae.blogia.com/temas/america.php

Un grupo de 13 torres de piedra que coronan la ladera de una montaña costera en Perú forman el observatorio solar más antiguo del hemisferio occidental, dijeron el jueves investigadores.

El emplazamiento de 2.300 años de antigüedad remite a una sofisticada cultura que usó el espectacular alineamiento del sol y las estructuras para efectos políticos y ceremoniales, agregaron.

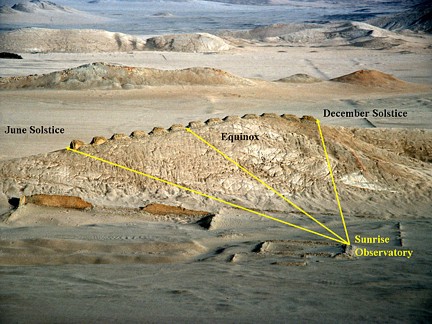

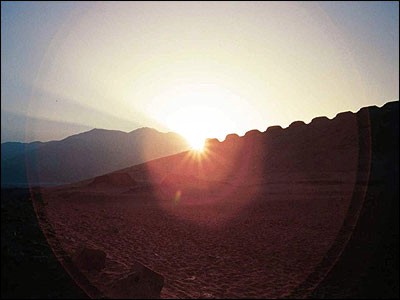

El lugar, denominado las Trece Torres de Chankillo, abarca con precisión los arcos anuales de salida y puesta del sol, cuando se les ve desde dos puntos de observación especialmente construidos para tal fin.

"Miles de personas podrían haberse reunido para observar impresionantes eventos solares. Estos acontecimientos podrían haber sido manipulados por una agenda política", dijo Ivan Ghezzi, quien hizo el descubrimiento mientras era estudiante de la Universidad de Yale.

Por ejemplo, durante la época del solsticio de verano en junio, el día más largo del año, el sol sale justo a la izquierda de la torre más septentrional, explicó Ghezzi, que ahora es el director arqueológico del Instituto Nacional de Cultura de Perú, en una entrevista telefónica.

Chankillo es un extenso centro ceremonial de varios kilómetros cuadrados. Tiene una estructura bien fortificada en la cima de la colina, gruesos muros y parapetos.

Pero nadie había entendido la presencia de una hilera de torres a lo largo de 300 metros, colocadas en una colina cercana, como espinas en la espalda de un dragón.

En un artículo en la revista "Science", Ghezzi y sus colegas dijeron que lo comprendieron.

"Desde el siglo XIX se especulaba con que la fila de 13 torres podría ser una demarcación lunar, pero nadie siguió esa pista", dijo Ghezzi, quien decidió probar la idea mientras estudiaba estructuras militares en el lugar, que datan del siglo IV antes de Cristo.

Ghezzi afirmó que se sabe muy poco sobre la gente que construyó Chankillo, pero habrían precedido a los Incas por varios siglos.

Al investigador no le sorprendió el hallazgo de un observatorio tan antiguo y afirma que Perú es una de las fronteras arqueológicas inexploradas en el mundo.

"Esta clase de conocimiento es esencial para la supervivencia, para navegar, para seguir animales y regresar a tu lugar de origen, para hacer un seguimiento de las estaciones", sostuvo Ghezzi.

"Tenemos que encontrar otras razones para explicar por qué un grupo de personas llegó tan lejos como para construir torres monumentales en la cima de una colina", concluyó.

Existen muchas evidencias que demuestran que los Incas usaron los movimientos del sol para demostraciones de poder con fines políticos.

Fuente: Maggie Fox / Reuters, 2 de febrero de 2007

Enlace: http://www.lagaceta.com.ar/

vernota.asp?id_seccion=10&id_nota=196321

El observatorio está formado por trece torres levantadas en línea, de norte a sur, sobre la cima del monte Chankillo. REUTERS /The fortified stone temple at Chankillo. Credit: National Aerial Service, Peru / COURTESY IVAN GHEZZI

ANCIENT SOLAR OBSERVATORY: The thirteen towers of Chankillo

ANCIENT SOLAR OBSERVATORY: The thirteen towers of Chankillo may constitute the oldest solar observatory in the Americas. Standing atop a hill in coastal Peru, the 2,300-year-old citadel is evidence that Sun cults predated the Incas by two millennia, researchers report in this week’s Science. When viewed from two observation points, the towers measure the annual rising and setting arcs of the sun with near-perfect accuracy. terraeantiqvae.blogia.com/temas/america.php

This image released by Yale University shows a diagram superimposed over what archaeologist from Yale and the University of Leicester claim is the earliest observatory in the Americas with alignments covering the entire year. The diagram shows how the observatory might have been used. Ivan Ghezzi from the Anthropology Department at Yale, lead author of a paper in Science magazine, writes that the 2,300-year-old site in Chankillo, Peru, predates the European conquest of the Americas by 1,800 years and similar construction by the Mayan by 500 years.(AFP-HO) COURTESY IVAN GHEZZI

(2) Peru ruins remains of 2,300-year-old solar observatory: study

Thu Mar 1, 7:46 PM ET

WASHINGTON (AFP) - Thirteen towers aligned on a hill in Peru are the remains of a 2,300-year-old solar observatory and calendar, which pre-dates even the Inca civilization, according to a study published Thursday.

The fortified stone temple at Chankillo. Credit: Courtesy of Peru’s National Aerophotographic Service (SAN) COURTESY IVAN GHEZZI

The walled, hilltop Chankillo ruins, some 400 kilometers (250 miles) north of Lima, have long puzzled scientists, says the study published in the March 2 edition of the US review Science.

But Peruvian archeologist Ivan Ghezzi and his British colleague Clive Ruggles now believe that the sequence of towers erected between 200 and 300 BC "marked the summer and winter solstices" and that Chankillo "was in part a solar observatory."

The towers "are built north-to-south on a hill in the center of the complex. Sites to the east and west are adorned with known relics of sacrificial material and were likely observing locations.

"From these sites, the towers mark the annual rising and setting arcs of the sun. They also serve as a calendar accurate to within a few days," Science reported.

The towers were evidence of earlier sophisticated sun cults than the Incans which were known to be carrying out studies of the sun some 1,500 years ago, it added.

Source: http://news.yahoo.com/s/afp/20070302/sc_afp/

usarcheologyperu_070302004636;_

ylt=Agdzjgy9XmON.7kd5WBRTdsTO7gF

(3) Peruvian citadel is site of earliest ancient solar observatory in the Americas

Archeologists from Yale and the University of Leicester have identified an ancient solar observatory at Chankillo, Peru as the oldest in the Americas with alignments covering the entire solar year, according to an article in the March 2 issue of Science.

Recorded accounts from the 16th century A.D. detail practices of state-regulated sun worship during Inca times, and related social and cosmological beliefs. These speak of towers being used to mark the rising or setting position of the sun at certain times in the year, but no trace of the towers has ever been found. This paper reports the earliest structures that support those writings.

At Chankillo, not only were there towers marking the sun’s position throughout the year, but they remain in place, and the site was constructed much earlier – in approximately the 4th century B.C.

"Archaeological research in Peru is constantly pushing back the origins of civilization in the Americas," said Ivan Ghezzi, a graduate student in the department of Anthropology at Yale University and lead author of the paper. "In this case, the 2,300 year old solar observatory at Chankillo is the earliest such structure identified and unlike all other sites contains alignments that cover the entire solar year. It predates the European conquests by 1,800 years and even precedes, by about 500 years, the monuments of similar purpose constructed by the Mayans in Central America."

Chankillo is a large ceremonial center covering several square kilometers in the costal Peruvian desert. It was better known in the past for a heavily fortified hilltop structure with massive walls, restricted gates, and parapets. For many years, there has been a controversy as to whether this part of Chankillo was a fort or a ceremonial center. But the purpose of a 300meter long line of Thirteen Towers lying along a small hill nearby had remained a mystery..

The new evidence now identifies it as a solar observatory. When viewed from two specially constructed observing points, the thirteen towers are strikingly visible on the horizon, resembling large prehistoric teeth. Around the observing points are spaces where artifacts indicate that ritual gatherings were held.

The current report offers strong evidence for an additional use of the site at Chankillo — as a solar observatory. It is remarkable as the earliest known complete solar observatory in the Americas that defines all the major aspects of the solar year.

"Focusing on the Andes and the Incan empire, we have known for decades from archeological artifacts and documents that they practiced what is called solar horizon astronomy, which uses the rising and setting positions of the sun in the horizon to determine the time of the year," said Ghezzi. "We knew that Inca practices of astronomy were very sophisticated and that they used buildings as a form of "landscape timekeeping" to mark the positions of the sun on key dates of the year, but we did not know that these practices were so old."

According to archival texts, "sun pillars" standing on the horizon near Cusco were used to mark planting times and regulate seasonal observances, but have vanished and their precise location remains unknown. In this report, the model of Inca astronomy, based almost exclusively in the texts, is fleshed out with a wealth of archaeological and archaeo-astronomical evidence.

Ghezzi was originally working at the site as a Yale graduate student conducting thesis work on ancient warfare in the region, with a focus on the fortress at the site.

Noting the configuration of 13 monuments, in 2001, Ghezzi wondered about a proposed relationship to astronomy. "Since the 19th century there was speculation that the 13-tower array could be solar or lunar demarcation — but no one followed up on it," Ghezzi said. "We were there. We had extraordinary support from the Peruvian Government, Earthwatch and Yale University. So we said, ’Let’s study it while we are here!’"

To his great surprise, within hours they had measurements indicating that one tower aligned with the June solstice and another with the December solstice. But, it took several years of fieldwork to date the structures and demonstrate the intentionality of the alignments. In 2005, Ghezzi connected with co-author Clive Ruggles, a leading British authority on archeoastronomy. Ruggles was immediately impressed with the monument structures.

"I am used to being disappointed when visiting places people claim to be ancient astronomical observatories." said Ruggles. "Since everything must point somewhere and there are a great many promising astronomical targets, the evidence — when you look at it objectively — turns out all too often to be completely unconvincing."

"Chankillo, on the other hand, provided a complete set of horizon markers — the Thirteen Towers — and two unique and indisputable observation points," Ruggles said. "The fact that, as seen from these two points, the towers just span the solar rising and setting arcs provides the clearest possible indication that they were built specifically to facilitate sunrise and sunset observations throughout the seasonal year."

What they found at Chankillo was much more than the archival records had indicated. "Chankillo reflects well-developed astronomical principles, which suggests the original forms of astronomy must be quite older," said Ghezzi, who is also the is Director of Archaeology of the National Institute of Culture in Lima, Peru.

The researchers also knew that Inca astronomical practices in much later times were intimately linked to the political operations of the Inca king, who considered himself an offspring of the sun. Finding this observatory revealed a much older precursor where calendrical observances may well have helped to support the social and political hierarchy. They suggest that this is the earliest unequivocal evidence, not only in the Andes but in all the Americas, of a monument built to track the movement of the sun throughout the year as part of a cultural landscape.

According to the authors, these monuments were statements about how the society was organized; about who had power, and who did not. The people who controlled these monuments "controlled" the movement of the sun. The authors pose that this knowledge could have been translated into the very powerful political and ideological statement, "See, I control the sun!"

"This study brings a new significance to an old site," said Richard Burger, Chairman of Archeological Studies at Yale and Ghezzi’s graduate mentor. "It is a wonderful discovery and an important milestone in Andean observations of this site that people have been arguing over for a hundred years."

"Chankillo is one of the most exciting archaeoastronomical sites I have come across," said Ruggles. "It seems extraordinary that an ancient astronomical device as clear as this could have remained undiscovered for so long."

Source: Yale University

Chankillo Observatory, Peru

Click here to view full image (3387 kb)

About 400 kilometers (250 miles) north of Lima, Peru, lies an enigmatic, 2,300-year-old ruin named Chankillo. Archaeologists have nicknamed the ruin’s central complex the “Norelco ruin” based on its resemblance to a modern electric shaver. The building’s true purpose long eluded them. Its thick walls and hilltop location suggested it was a fort, but why, researchers wondered, would anybody build a fort with so many gates and without a water source? Then in March 2007, two researchers, Ivan Ghezzi and Clive Ruggles, offered an explanation for the complex: at least part of it was a solar observatory.

GeoEye’s IKONOS sensor captured this image of Chankillo on January 13, 2002, and this picture shows the features the archaeologists studied to infer the site’s purpose. The central complex appears in the upper left with its concentric rings of fortified walls. Southeast of the central complex are the Thirteen Towers, which vaguely resemble a slightly curved spine. On either side of the towers are observing points (little is left of the eastern observation structure), and south of the eastern observing point is another building complex, apparently used in part for food storage. Although the dark shapes in the northeast seem like rock outcrops, the higher-resolution image reveals they are probably trees.

The Thirteen Towers were the key to the scientists conclusion that the site was a solar observatory. These regularly spaced towers line up along a hill, separated by about 5 meters (16 feet). The towers are easily seen from Chankillo’s central complex, but the views of these towers from the eastern and western observing points are especially illuminating. These viewpoints are situated so that, on the winter and summer solstices, the sunrises and sunsets line up with the towers at either end of the line. Other solar events, such as the rising and setting of the Sun at the mid-points between the solstices, were aligned with different towers.

Why did the ancient inhabitants of this region cultivate such a thorough understanding of solar cycles? In addition to potential ceremonial purposes, the observatory may have had practical uses as well. In Peru’s dry coastal reason, precipitation is seasonal, so a reliable solar calendar would help determine the optimal time to plant crops.

Further reading:

Mann, C. C. (2007). Mystery Towers in Peru Are an Ancient Solar Calendar. Science. 315: 1206-1207.

Ghezzi, I., and Ruggles, C. (2007). Chankillo: A 2300-Year-Old Solar Observatory in Coastal Peru. Science. 315: 1239-1243. Image copyright GeoEye/SIME.

Link: http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Newsroom

/NewImages/images.php3?img_id=17620

]]>