Secesión de Sudán beneficia a EEUU y China

Behind the internal rivalry in Sudan were U.S. and China's energy interests, but the two superpowers reached agreement.

Detrás de la rivalidad interna de Sudán se encontraban los intereses energéticos de China y Estados Unidos, pero ambas superpotencias alcanzaron un acuerdo por medio del cual se beneficiarán de las cuantiosas reservas petroleras del Estado naciente de Sudán del Sur.

La mayor parte de las guerras étnicas africanas del siglo XX y XXI no han sido originadas por ancestrales odios tribales, como sugieren algunos analistas. Por el contrario, estas rivalidades entre poblaciones fueron exacerbadas desde el inicio de la colonización, que derivó del reparto de África en la Conferencia de Berlín de 1885.

---

Nace Sudán del Sur con el apoyo de China y EE.UU.

por Maximiliano Sbarbi Osuna |

13-1-2011 - En los próximos días nacerá una nueva nación en África: Sudán del Sur. Los años de guerra civil entre el Norte y la zona meridional dejaron más de 2 millones de muertos. Detrás de la rivalidad interna se encontraban los intereses energéticos de China y Estados Unidos, pero ambas naciones alcanzaron actualmente un acuerdo por medio del cual se beneficiarán de las cuantiosas reservas petroleras del Estado naciente. ¿Es viable la vida autónoma de este nuevo país? ¿Puede reactivase la guerra civil?

La silueta de habitantes de Sudán del Sur se ve a través de una bandera mientras esperan para votar si se separan del norte - AP

La mayor parte de las guerras étnicas africanas del siglo XX y XXI no han sido originadas por ancestrales odios tribales, como sugieren algunos analistas. Por el contrario, estas rivalidades entre poblaciones fueron exacerbadas desde el inicio de la colonización, que derivó del reparto de África en la Conferencia de Berlín de 1885.

La celebración del referéndum independentista de Sudán del Sur es el resultado de un conflicto geopolítico, protagonizado por Estados Unidos y China, que gira en torno a las cuantiosas reservas petroleras de Sudán.

ESTADOS UNIDOS VS. CHINA

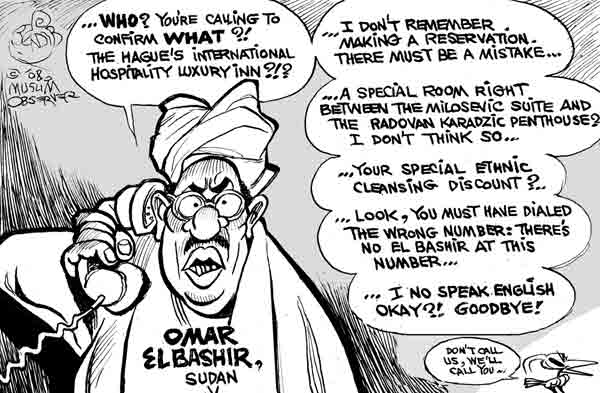

Pekín es un voraz comprador de petróleo, que ha establecido contactos comerciales desiguales con casi todos los países africanos para proveerse principalmente de los recursos energéticos que sustenten a sus expansivas industrias. Esto lo ha llevado a sostener al dictador de Sudán, Omar Al-Bashir, que está en el poder desde el golpe de 1989.

El Norte de Sudán, compuesto mayoritariamente por árabes y musulmanes, domina al Sur del país, que está poblado por diversas tribus negras, de religión cristiana y animista. Al-Bashir dirige al país, con el apoyo económico y militar de China, desde Jartum, la capital que se encuentra ubicada en el Norte. A cambio, Sudán le otorga el petróleo que Pekín necesita.

En tanto, en el Sur se encuentran alrededor del 80% de las reservas de petróleo de las que el Norte se beneficia, ya que posee la infraestructura para el proceso del crudo y además los gasoductos para la exportación. La inequitativa distribución de las regalías que aportaban los hidrocarburos fueron los que encendieron la mecha del conflicto armado Norte-Sur.

Durante la Segunda Guerra Civil sudanesa (1983-2004), las empresas occidentales se alejaron de Sudán por la inseguridad que generaba el conflicto. Sin embargo, China se fue acercando de a poco y armando al gobierno del Norte, que es el que tiene la llave del petróleo del Sur.

Paralelamente, Washington, a través de países aliados como Kenia y Etiopía, proveía de armas a la guerrilla sureña Ejército Popular de Liberación de Sudán (SPLA), comandada por John Garang. Pero en 1998, luego de la voladura de las embajadas norteamericanas en Kenia y Tanzania, el gobierno de Bill Clinton reaccionó bombardeando unas instalaciones sudanesas en las que de acuerdo con Estados Unidos se producían armas químicas, pero según Sudán, era un laboratorio que elaboraba medicamentos.

Otro motivo de la rivalidad entre Washington y Al-Bashir surgió entre 1994 y 1996, cuando Sudán le brindó asilo a Osama Bin Laden.

De esta manera, con el financiamiento de ejércitos opuestos, detrás de la Segunda Guerra Civil, se encontraba la lucha por el petróleo entre Estados Unidos y China.

ACUERDO DE PAZ Y NUEVA GUERRA FRÍA

La Segunda Guerra Civil dejó alrededor de 2,5 millones de muertos y unos 5 millones de desplazados al exterior, mientras que los refugiados internos también se cuentan en millones. El final de la guerra llegó en 2004, pero recién un año después se formó un gobierno de coalición con Al-Bashir como presidente y Garang como vicepresidente, pero un accidente de helicóptero se cobró la vida del líder sureño a tan sólo veinte días de haber asumido. En ese momento, se temió un resurgimiento de la guerra civil, pero Garang fue reemplazado por el actual líder del Sur, Salva Kiir.

El acuerdo contempló que los dividendos producidos por el petróleo se repartirían en partes iguales, mientras que el ejército del Norte se retiraría del Sur en un plazo de dos años, al igual que las guerrillas comandadas por Kiir de los territorios norteños. Este convenio de paz estuvo vigilado por los Cascos Azules de la Misión de la ONU en Sudán (UNMIS). Además, se previó un referéndum, que es el que se está desarrollando en este momento, y por el cuál el Sur decidiría su independencia.

Pero las estrategias chinas y norteamericanas no se detuvieron con la tregua. Washington bloqueó la actividad petrolera sudanesa penalizando a las empresas que extrajeran el crudo. Además, promovió que el Tribunal Penal de La Haya lo procesara por genocidio en otro frente de combate abierto que tiene en la región occidental de Darfur.

Al mismo tiempo, China, previendo que era posible la independencia de Sudán del Sur, comenzó a construir un oleoducto de 1.400 kilómetros que va a conectar esta región meridional con el Océano Índico, a través de Kenia. Entre tanto, incrementó los contactos diplomáticos con los líderes del Sur, para asegurarse las ganancias petroleras de un futuro Estado. Además inició una desinversión en Sudán del Norte, para no quedar atado al aislado gobierno de Al-Bashir, que aún mantiene el apoyo de la Liga Árabe y de la Unión Africana, y diversificar así las fuentes energéticas.

Por otro lado, días atrás el senador demócrata norteamericano, John Kerry, viajó a Jartum para llevarle a Al-Bashir una propuesta que consiste en que si acepta un Sudán del Sur independiente, Washington va a retirar a su gobierno de la lista de los patrocinadores de terrorismo, aunque aún quede pendiente el genocidio de Darfur.

¿ES POSIBLE UN GOBIERNO INDEPENDIENTE EN SUDÁN DEL SUR?

Los resultados del plebiscito que se está llevando a cabo durante esta semana seguramente se conocerán en febrero, pero lo más probable es que el Sur alcance su independencia. Al-Bashir prometió que va a respetar la decisión, pero que aumentará la Sharía o Ley Coránica en el Norte, una de las causas de la Segunda Guerra Civil.

El nuevo Estado va a nacer empobrecido, ya que a pesar de disponer de grandes reservas de petróleo, su economía se basa en la agricultura de subsistencia. Por eso, debe acordar con el Norte la exportación del hidrocarburo por los oleoductos ya existentes, que son administrados por Jartum. Además, deberá profundizar las relaciones con China y abrir nuevamente las inversiones a las petroleras norteamericanas y europeas.

Pero, muchos dudan de la capacidad de que Sudán del Sur se autogestione, ya que en seis años de gobierno autónomo, la mitad de las regalías petroleras no aportaron beneficios para la población, dado que, en su mayoría, el presupuesto fue utilizado en armas y en pagos de salarios a los soldados.

Además, se prevé un regreso masivo de refugiados, que ya se está percibiendo durante las elecciones. El nuevo país deberá afrontar la afluencia de cientos de miles de personas que intentarán volver a su tierra en paz.

Por otro lado, la conformación cultural del nuevo Estado es compleja. Existen unos 17 millones de habitantes divididos en 500 tribus, que hablan 110 idiomas diferentes. Si el resultado de la consulta es positivo para el Sur, en julio nacería la nueva nación.

Así, tanto China como Estados Unidos llegaron a un acuerdo al limitar a Al-Bashir y promover el desarrollo y las relaciones con Sudán del Sur, en el que ambos países se van a beneficiar de las reservas petroleras para satisfacer a sus poderosas industrias.

¿Puede haber una tercera guerra civil?

Algunos analistas dudan de que Al-Bashir acepte la partición del país, dado que Sudán del Norte perdería el 80% de su petróleo. Pero los incentivos chinos y norteamericanos, sumados a la presión internacional, van a persuadir al dictador.

Aunque, aún falta definir las fronteras definitivas entre ambos países, el reparto de la deuda externa, el transporte y la exportación del petróleo y el caudal del agua del Nilo Blanco.

Todavía hay territorios fronterizos en los que no se ha realizado la consulta y cuyos pobladores se encuentran divididos. En la zona de Abyei, que por ahora va a quedar del lado del Norte, se encuentran enormes reservas petroleras y de agua dulce.

Allí viven los Dinka, agricultores de origen negro, y los Baggara, de origen árabe. Estos últimos, se dedican al ganado y son nómades, por eso aprovechan las tierras en época seca. Ya se han producido sangrientos enfrentamientos entre estas dos comunidades, dado que los Baggara atraviesan el territorio para llevar al ganado a pastar, pero no tienen ningún derecho sobre la tierra.

Un enfrentamiento entre ambas tribus podría reavivar la Guerra Civil, aunque también existen situaciones similares en los estados de Nuba y Nilo Azul, que deberán decidir su futuro más adelante, mientras tanto dependerán de Jartum.

Aún las cicatrices de tantos años de guerra no han cerrado. Desde el viernes pasado, se han producido más de 60 muertos en Abyei, en un enfrentamiento entre milicias que apoyaban el referéndum y las que lo rechazaban. Además, la ONU anunció que su misión en Sudán no se encuentra capacitada para detener un nuevo enfrentamiento civil.

Por ahora, esta nueva nación va a emerger con el apoyo de la comunidad internacional, pero deberá resolver los enfrentamientos entre las poblaciones fronterizas y varios temas vitales con el gobierno de Al-Bashir.

Sudaneses de la etnia Toposa celebran la secesión del país, cerca de la frontera con Kenia. Desde la independencia de ese país, en 1956, hubo profundas diferencias sociales, confrontaciones interétnicas y problemas religiosos entre las regiones norte y sur.

Sudán del Sur aprueba la secesión por 98,83% de los votos (oficial)

lunes, 7 de febrero

El 98,83% de los electores de Sudán del Sur votó en favor de la secesión, según los resultados oficiales definitivos publicados el lunes por la comisión electoral del referéndum.

Este anuncio era una simple formalidad dado que según los resultados preliminares completos publicados el 30 de enero, el 98,83% de los sursudaneses habían votado a favor de la independencia en su región, llamada a convertirse en un Estado independiente.

Los resultados, expuestos en pantallas durante una ceremonia en Jartum, muestran que sobre 3.837.406 votos válidos, sólo 44.888, es decir el 1,17%, estaban en favor de mantener la unidad con el Norte.

Por la mañana, el presidente sudanés Omar al Bashir había declarado: "Los resultados del referéndum son bien conocidos. Sudán del Sur eligió la secesión. Pero nos comprometemos a mantener los vínculos entre el Norte y el Sur y (...) a mantener buenas relaciones basadas en la "cooperación".

Por su parte, el presidente Barack Obama anunció este lunes que Estados Unidos reconocerá al Sudán del Sur "soberano e independiente" en julio próximo, y felicitó a sus habitantes por haber votado a favor de la independencia durante un referendo "histórico".

"En nombre de los estadounidenses, felicito a los habitantes de Sudán del Sur por un referendo coronado por el éxito, durante el cual la mayoría aplastante de los votantes eligió la independencia", indicó en un comunicado el presidente Obama.

"Estoy, pues, feliz de anunciar la intención de Estados Unidos de reconocer formalmente a Sudán del Sur como Estado soberano e independiente en julio de 2011", agregó el presidente norteamericano.

www.dipity.com/chesterrhoder/South-Sudan-Info-3/

6/jan/2011 - Pro-separation activists hold signs and chant pro-independence slogans outside the Juba airport in southern Sudan as Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir arrived

6/jan/2011 - Pro-separation activists hold signs and chant pro-independence slogans outside the Juba airport in southern Sudan as Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir arrived

Flag dance

A southern Sudanese man dances during a rally in the southern capital Juba on Jan. 7, 2011. Sudan is heading for an acrimonious split in a Jan. 9 referendum on secession for the south.

But while southern leaders want political independence from the north, economic realities might keep them uncomfortably dependent on their former foes.

Most analysts expect the south, which accounts for almost 75 % of the 500,000 barrels of oil that Sudan produces per day, to secede after the referendum, which came out of a 2005 peace deal ending Africa's longest civil war. Independence would take effect on July 9.

The ballot

Judge Chan Reec Madut, the chairman of the Southern Sudan Referendum Bureau, discusses the referendum ballot during a press conference in Juba, southern Sudan. (Pete Muller/Associated Press)

Failure of diplomacy: Southern Sudan's secession next step of change in Africa

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Why does southern Sudan want independence?

Spencer Platt / Getty Images

Women walk home to their village with water on the outskirts of the southern Sudanese city of Juba on Jan. 6.

Like much of Africa, Sudan’s borders are a legacy of colonial powers and have little regard for the vast cultural and religious differences that divide north and south. The north is mostly Muslim and is dominated by Arab influences, while the south is largely Christian or animist and is more close culturally to Kenya, Uganda and other sub-Saharan nations.

With the Arab-dominated central government based in the north, in Khartoum, many southerners feel that they have been discriminated against and oppose moves to impose Islamic law across the country.

Putting Sudan on the map

Sudan is Africa's largest country and the tenth largest country in the world. While the Nile runs through the country, the climate is divided by arid desert in the north and lush tropics in the south.

Who can vote?

Men sit on a bus as they arrive for a rally in Juba, South Sudan's largest city, on Jan. 4.

Only southern Sudanese are eligible to vote, which is why many analysts believe the outcome will be secession. Out of the nearly 4 million people who have registered to vote, more than 95 percent live in southern Sudan, the rest are southern Sudanese living in the north or in one of eight foreign countries. For the referendum to be considered valid, 60 percent of voters must take part. Voting begins Jan. 9 and will last for seven days.

What are the key issues?

Pete Muller / AP

Southern Sudanese security forces wait outside the control room of the Petrodar oil facility in Paloich, southern Sudan on Nov.17, 2010. Sudan is sub-Saharan Africa's third-largest oil producer, behind Nigeria and Angola. It produced 490,000 barrels of oil a day last year. Most of the oil is in the south. But the pipelines run through the north.

Oil. Sudan’s economy has boomed in recent years, thanks to billions of dollars in oil exports. Sudan is now sub-Saharan Africa's third-largest oil producer, behind Nigeria and Angola. The south produces an estimated 75 percent of Sudan’s crude oil, but receives only 50 percent of the revenue, which is split with the government in Khartoum, fueling some of the animosity toward the north.

But the south is landlocked – and the pipelines to export oil run through the north to the Red Sea. After two decades of war, the south’s infrastructure is severely lacking – with few paved roads, schools or factories. Southern leaders have invested in rebuilding, but they seem to recognize that they will have to continue working with the north and share the oil if they want to continue reaping the profits.

China is also heavily invested in Sudan’s oil, so it has a vested interest in the referendum’s outcome. China is Sudan’s largest trading partner – 58 percent of its exports, predominately oil, head to Beijing, according to the CIA World Factbook.

One oil-rich area, Abyei, is not included in the referendum. It will hold a separate vote later to decide which country it will be a part of.

Who are the leaders?

GORAN TOMASEVIC / Reuters

South Sudan's President Salva Kiir, left, and Sudan's President Omar Hassan al-Bashir, right, review an honor guard at the airport in Juba Jan. 4.

Sudan’s President Omar Hassan al-Bashir seized power in a military coup in 1989 and has ruled the country with an iron fist ever since. The International Criminal Court in The Hague has issued two international arrest warrants for him on the charges of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity. The charges stem from the conflict in western Darfur, where hundreds of thousands of people have been killed or displaced by the fighting between government and rebel forces.

Bashir was also the driving force behind the brutal civil war with the south, which killed an estimated 2 million. Nevertheless, Bashir visited the south before the vote and offered support for the historic referendum. “I personally will be sad if Sudan splits,” Bashir said in a speech in the southern capital of Juba on Jan. 4. “But at the same time I will be happy if we have peace in Sudan between the two sides. We cannot deny the desire and the choice of the people of the south. This is their right.”

Salva Kiir is the president of southern Sudan (it has been a semiautonomous region since the peace treaty was signed in 2005). Kiir, whose signature look is a cowboy hat, is a former rebel and leader of the Sudan People's Liberation Movement. He is extremely popular in the south and won 93 percent of the most recent election, in April 2010. He favors full independence for the south and is expected to be the leader of the new country if it secedes.

What is the United States view of the referendum?

MOHAMED NURELDIN ABDALLAH / Reuters

U.S. Senator John Kerry walks with Sudanese presidential adviser Nafi Ali Nafi after a meeting at the presidential palace in Khartoum on Jan. 5. Kerry told reporters that the U.S government looks forward to success in Sudan's referendum.

As one of the parties involved with negotiating the 2005 peace treaty to end the civil war, the United States has pledged its support to south Sudan if it votes to secede.

"The United States has invested a great deal of diplomacy to ensure that the outcome of this referendum is successful and peaceful," Assistant Secretary of State Johnnie Carson, the Obama administration's top diplomat for Africa, told reporters in Washington on Jan. 5. "We will also as a country help that new nation to succeed, get on its feet and to move forward successfully, economically and politically."

Will there be international observers?

Pete Muller / AP

Justice Chan Reec Madut, the chairman of the Southern Sudan Referendum Bureau, shows off the referendum ballot during a press conference in Juba, southern Sudan on Jan. 3.

The vote will be closely scrutinized by more than 3,000 international and domestic observers. U.S. Senator John Kerry has already arrived in Sudan and will be joined by former U.S. president Jimmy Carter and former U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan as part of the Carter Center's 100-strong observation delegation. Actor George Clooney and activist John Prendergast will also be on hand. China, which has invested heavily in Sudanese oil development, is also sending observers.

------------------------------------------------------------

2005 CPA did not address Darfur conflict: Sudan advisor

2005 CPA did not address Darfur conflict: Sudan advisor

Feb 19, 2011 2 AM Sudan’s 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), signed between the north and former rebels in the south was a “mere ceasefire” agreement that largely ignored issues like the Darfur conflict, John Ashworth, an advisor on Sudan told Sudan Tribune. Signed in Naivasha, Kenya, the CPA ended over two decades of bloody civil war fought between Christians in the South and Muslim and Arab-dominated north Sudan. Nearly 2.5 million died during the war, according to UN estimates, while over 4 million were displaced. “The 2005 CPA, as I have argued before here and elsewhere is neither a comprehensive nor a peace accord. It was simply a cease-fire agreement between only two parties in only one of the conflicts in Sudan signed under intense international pressure,” Ashworth said. The accord, Ashworth added, never addressed certain key post-conflict issues, citing the recent instabilities that have rocked the southern region. Last week, clashes between the southern army and rebels loyal to renegade General George Athor killed over 200 people. “As you know, the CPA was signed between mainly two political parties, largely ignoring the interest of the others. In the same way, some of the political and military factors currently destabilizing the south need to be dealt with in accordance with the provisions of the this same peace accord,” said Ashworth, who has over 20 years experience working in Sudan. However, he remains optimistic that the ongoing post-referendum negotiations between the two parties, on the fate of Abyei referendum, north-south border demarcation and issues of oil revenue sharing will be resolved amicably. On the fate of the church, Ashworth predicted that northern churches would face persecution after the South secedes. But he believes that Christianity will flourish south, with a rapid expansion of churches after the independence declaration in July. He said, “With the independence of the south forthcoming, I think churches in the north will suffer from the strict sharia laws that the northern government plans to adopt. Northern churches will become smaller and severely persecuted while those in the South will expand.” Ashworth expressed sympathy for Church leaders in the north and their followers. He urged Christians in Sudan to develop strong moral values based on freedom, democracy and equal participation for all. By Julius N. Uma photo: John Ashworth, an advisor on Sudan during an interview with Sudan Tribune. Feb 17, 2011 (ST)

http://www.sudantribune.com/2005-CPA-should-have-addressed

Update: Proposed Cuts to Aid Risk Lives in Sudan

Update: Proposed Cuts to Aid Risk Lives in Sudan

Feb 18, 2011 1 PMStatus of House Bill that Cuts Sudan Aid Earlier this week, we raised the alarm about cuts to humanitarian aid that would drastically impact life-saving assistance to Sudan and Darfur. Based on expenditures made to support humanitarian operations last fiscal year, we have calculated that the proposed cuts could put more than $200 million of aid for Darfur and Sudan on the chopping block. The reductions were made by the House of Representatives through House Bill 1 (H.R.1), which is still being debated on the floor today. This afternoon House Majority Leader Eric Cantor (R-VA) promised a vote on H.R.1 before the chamber adjourns for the week-long Presidents Day recess. The vote could come late this evening or even move into Saturday morning. If you haven’t already, you can still take action to support life-saving money for Sudan by urging your representative to vote NO on H.R.1 unless humanitarian aid is restored. The Next Stage in the Fight to Restore Aid Given the reality that the current spending bill will run out on March 4, the House is determined to pass a bill to provide funding for the rest of the fiscal year before next week’s recess. Then the fight will continue in the Senate where leaders are pushing for a short-term extension to give Congress more time to reach agreement between the two chambers. Both the House and Senate are set to return from recess on February 28 and–given the drastic differences in funding priorities between the House and Senate–it is unlikely that a bill could be passed in the Senate and the two versions reconciled by the end of the week. If an extension isn’t passed or a reconciled bill isn’t agreed upon by both the House and Senate there will be a government shutdown. We will be following the latest developments over the next couple of weeks as we fight for the restoration of humanitarian aid and will keep you updated. by Allyson Neville-Morgan

http://blogfordarfur.org/archives/7444

http://www.economist.com/blogs/baobab/2011/02/revolutions_sudan

Feb 18, 2011 10:27 AMIT IS a measure of just how uncomfortable Sudan’s awful president, Omar al-Bashir, must be feeling right now that a few days ago he promised his impoverished and downtrodden people that he would give them all "internet, computers and Facebook". I doubt Mr Bashir has ever set eyes on a Facebook page—but he certainly knows that whatever it is, it is something to be reckoned with, given recent events in neighbouring Egypt. Whereas Muammar Qaddafi has tried to ban the pesky revolutionary networking site in Libya, Mr Bashir seems to be trying the opposite tactic in Sudan. I doubt it will help him very much—and if his past promises are anything to go by, we can be pretty certain that almost no one will get a broadband connection, let alone ever get to see Facebook. Of all the ageing dictators in north Africa and the Middle East, Mr Bashir certainly knows the most about the potent threats of people power and popular uprisings—he has lived through two of them in Sudan. The first took place in 1964: the so-called "October revolution" ousted newly independent Sudan’s first military dictator, General Aboub. The second occurred in 1985 and toppled another military dictator, Jafar Numeiri, who had come to power in a coup in 1969. It is this uprising that will be preying on Mr Bashir’s mind today. Last year I sat down for a chat with the man who inadvertently became the leader of that revolt, an amiable and mild-mannered lawyer called Omer Abdel Ati. He explained to me what happened. Events unfolded in a remarkably similar fashion to what has just happened in Egypt. Tens of thousands of people spontaneously gathered in central Khartoum for days of protests, their numbers swelling as the uprising gathered steam. Like in Egypt, nothing was planned, and there were no specific leaders or political parties provoking the revolution. Mr Ati ended up as the figurehead for the revolt merely by virtue of the fact that he happened to be head of the Sudanese Bar Association at the time, and many of the middle-class trade unions were in the vanguard of the revolution—lawyers, doctors, bankers, academics and the like. The reasons that so many people took to the streets will also be familiar. The economy was in dire straits; decades of economic mismanagement had left thousands of young people unemployed and disillusioned. There was a full-blown famine in the western province of Darfur; starving refugees wandered the streets of Khartoum. On top of this years of political repression had left the middle classes angry and resentful, hence the very active involvement of otherwise respectable professionals. Numeiri, like Mubarak, had relied on the army to keep a lid on things, helped along by large amounts of American aid money. But, faced by the size and determination of the 1985 uprising, the generals caved in, ironically while Numeiri was on a visit to Washington to see his great supporter Ronald Reagan. They declared an interim government, which paved the way for democratic elections the following year. After Mr Bashir and the Muslim Brotherhood launched their own coup in 1989, they spent the first few years of their rule specifically trying to eradicate those people and organisations that had risen up so effectively in 1985. Thus the middle-class trade associations and unions were closed down; many doctors and lawyers fled overseas. Student unions were closed and academics sacked. The new secret police tortured and killed many of those who had participated in the 1985 revolt. However much Mr Bashir thinks he can control things, the idea of a popular uprising still exercises a powerful hold on the Sudanese imagination. In 2005 the shanty-towns on the fringes of Khartoum rose up in days of rioting and looting after the death in a helicopter crash of the southern Sudanese rebel leader, John Garang. The following year there were sporadic riots in the capital over rising food prices; in 2008 one of the Darfur rebel groups launched an audacious attack on Omdurman, next to Khartoum, in the hope that it would spark a more general revolt against Mr Bashir’s regime. In the last week or so there have been occasional protests, involving no more than a few thousand people, but clearly modelled on the recent Egyptian and Tunisian experiences. The secret police acted swiftly, detaining student leaders, and even some opposition politicians, for short amounts of time. Even in the good times, Khartoum was closely monitored to prevent another 1985; all bridges have two "technicals" at either end with loaded machine-guns ready to fire on any protesters, and the main bridge from Khartoum to Omdurman has three tanks permanently stationed at the Omdurman end. I have not been there this year, but I would imagine this security has been beefed up. However, Mr Bashir knows he is vulnerable. An election victory last year was certainly no measure of his popularity; the polls were comprehensively rigged and the main opposition parties boycotted the whole process. Although an influx of oil money has benefited the president and the ruling elite, most north Sudanese, let alone Darfuris, are probably as poor and disadvantaged as when Mr Bashir came to power 22 years ago. Importantly, Mr Bashir has also just lost the south of his country to an overwhelming rejection of his rule, diminishing his reputation among his own supporters. Oh, and he’s also wanted by the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity. The circumstances, therefore, are certainly there for another 1985-style revolt, even if the regime long ago took plenty of precautions against just such an eventuality. It would be wonderful if it did happen; Sudan, perhaps even more than Egypt, desperately needs a new beginning. One of the most talented and creative peoples of Africa deserves it.

http://www.economist.com/blogs/baobab/2011/02/revolutions_sudan

SNB, Swiss Govt Help South Sudan Set Up Central Bank

Feb 18, 2011 6 AMZURICH (Dow Jones)--The Swiss National Bank and the country's Department of Foreign Affairs are helping the soon-to-be-independent state of South Sudan establish a central bank authority. Banking and financial officials from South Sudan, an oil-rich area but still one of the least-developed regions ...

http://online.wsj.com/article/BT-CO-20110218-704529.html

Feb 18, 2011 12 AMHow Egypt’s uprising could cause the utter disintegration of its neighbor. As protests inspired by the Egyptian uprising spread throughout the Middle East, there has been a lot of speculation about what government might fall next. Could it be Bahrain? Or Libya? Or Yemen? In fact, one of the governments that might, over the long run, be most vulnerable isn’t really on anyone’s radar at the moment. I am referring to the government of Sudan. But here’s the catch: While the events in Egypt could very well start a chain reaction that would lead to the downfall of the current Sudanese regime, it won’t happen in the obvious way—with protesters massing in the streets and demanding the ouster of a longtime dictator. Instead, the events in Egypt are likely to accelerate a process that is taking place anyway: the ongoing fracturing of northern Sudanese society—a fracturing that could be a prelude to civil war. To understand how this might happen, you first have to grasp the complicated politics of northern Sudan (the southern part of the country is soon to be under the rule of an entirely different government, having recently voted for independence). At the most basic level, the north is divided into two camps. On one side are Islamists and Arab nationalists; on the other are an array of secularists, socialists, African Sudanese, and democratic progressives who demand that the Northern Nile River elites share power in a secular democratic state. But within the Islamist and Arab nationalist camp, there is a further split: between the National Congress Party, led by current President Omar Al Bashir; and the more strident Islamists, who follow Hasan Al Turabi, one of the founders of the country’s Muslim Brotherhood. Originally, Bashir and Turabi were allies. They came to power together in a 1989 coup. Bashir became the head of government, though Turabi had been the coup’s mastermind. Together, the two men established the first Sunni Islamist state; extended Sharia law (first imposed by the former Sudanese dictator Numayri) through a new Islamist court system; Islamized the financial and banking systems; and prosecuted a brutal war in the Christian, non-Arab south in which more than two million people died. They also invited virtually every violent Islamist group in the world to base their operations and training camps in Sudan. Six months after taking power, Turabi orchestrated a long-term alliance between Iran and Sudan; they remain among each other’s closest allies. It was Turabi who invited Osama bin Laden to live and work in Sudan during the 1990s. Bin Laden married Turabi’s niece, and went into business with Turabi’s son, trading in Arabian horses. Gradually, however, Bashir and his party, the National Congress Party (NCP), moved away from Turabi’s radicalism. While Turabi was a true militant, it soon became clear that the only thing the NCP is militant about is their own survival. In 1995, an offshoot of the Muslim Brothers, the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, attempted to assassinate Egyptian President Mubarak at an Organization for African Unity conference in Addis Ababa. Egyptian intelligence believed the plot was orchestrated by Turabi. Sudan and Egypt nearly went to war over the incident, but ultimately Bashir decided to de-escalate tensions with Mubarak and distance himself from Turabi. A year later, bin Laden was expelled from Sudan because of pressure from the United States and Saudi Arabia, and Turabi was forced to find a home for his friend in Afghanistan. By 1999, Sudan’s two major political figures were locked in a raw power struggle: Turabi, as speaker of the National Assembly, attempted to reduce Bashir’s constitutional powers and increase his own, causing a bitter rift between the two men, which led to Turabi’s ouster. Since 2000, Turabi has been repeatedly imprisoned whenever he threatened or attacked the Bashir government. Turabi’s purge healed the breach between Sudan and Egypt, and Mubarak’s government vowed that it would never allow Turabi to rule Sudan again. To this day, the quarrel between Turabi and Bashir continues to divide Sudan’s Islamist movement. The Bashir government fears Turabi and his acolytes more than any other domestic opposition group, probably because they share the same base of support. Turabi claims the loyalty of perhaps half of the officer corps of the Sudanese army, and his supporters are the best organized among the country’s opposition. In May 2008, a Darfuri Islamist rebel group led by Khalil Ibrahim—who in the past has called Turabi his political godfather and has had a warm relationship with him, although he now disavows any link—drove 800 miles across the desert from the Chad border, with 2,000 troops and heavy weapons, to attack Khartoum and attempt to overthrow Bashir and his party. Ibrahim’s men fought their way to the Nile River Bridge near the presidential palace, where they were turned back by internal security forces in heavy street-to-street fighting—the first in Khartoum since 1973. Bashir was shaken by the incident and promptly arrested Turabi, who he believed was behind the attack. At the same time that Bashir has struggled to keep Turabi and his other erstwhile allies at bay, he has also had to deal with the non-Islamist, non-Arab opposition inside Sudan. Even with the secession of the African and Christian South, 45 percent of the new northern Sudanese state remains non-Arab and resents the domination of the country by the Northern Nile River Arabs and Islamism. Although most of the north is Muslim, the Sufist Islamic tradition—which opposes or remains ambivalent about an Islamist state—claims the devotion of a much larger portion of the population than Salafist Islam. Turabi’s political party, which grew out of the Muslim Brotherhood, never received more than 18 percent of the vote in national elections. So, for the past few decades, Bashir has navigated uneasily between these two powerful constituencies: his fellow Islamists and the opposition. Now, however, two recent events may prompt Bashir to abandon this careful balancing act. The first was south Sudanese succession. Under the terms of a North-South peace agreement brokered by the United States, Bashir agreed to let southern Sudanese voters choose whether they wanted to separate from the north in a January 2011 referendum. (On February 7, it was announced that 98 percent of southerners had voted for secession.) Alongside rising food prices, a heavy debt burden, and a major reduction of oil revenues (75 percent of Sudanese oil reserves and production are in the south), this alienated Bashir’s Islamist base, which attacked him for acquiescing to the referendum. Probably in response, Bashir vowed three weeks before the vote that, should the South secede, he would amend the constitution to declare northern Sudan an Arab Islamic state. The second event is the fall of Mubarak. Egyptian hostility to Turabi and his brand of Islam forced Bashir and his party to distance themselves from the radical Islamist agenda. Bashir remains determined to marginalize Turabi (whom he recently put in prison again) and to win the struggle for the Islamist base. For years, his alliance with Mubarak provided one of the main breaks on just how far he could go in appeasing the Islamists. Now that constraint is gone. And, if the Muslim Brotherhood gains significant power in Egypt, that could provide even more reason for Bashir to tip further toward Islamism. While such a strategy might preserve Bashir’s power in the short term, it could lead to disaster in the long term. By trying to secure his Islamist and Arab base, Bashir will only be setting the stage for a new civil war in the north. The Beja people to the east, the tribes of the Nuba Mountains, the Ngok Dinka in Abyei, the Funj in Blue Nile province, and the rebellious Darfur tribes do not want Sharia law or an Islamist state in Sudan, whether it is led by Turabi or Bashir. And they will go to war to prevent it, even if it means the dissolution of the new northern Sudan state. by Andrew Natsios

http://www.tnr.com/article/world/83366/egypt-sudan-protest-revolution-darfur

--