Hace 12,000 años ya se organizaban banquetes funerarios comunitarios

Scientists have found the earliest clear evidence of organized feasting, from a burial site dated about 12,000 years ago.

Cueva sepulcral en Galilea: La tumba de una chamán que data de hace unos 12.000 años, recamada de conchas de tortuga que evidencia un festín funerario.

.

Hace unos 12.000 años, en una pequeña cueva iluminada por el sol del norte de Israel, los congregados terminaban un banquete de carne de tortuga asada y reunían las decenas de caparazones negros restantes. De rodillas al lado de la tumba abierta en el suelo de la cueva, tributaron sus últimos respetos a la anciana muerta enroscada en posición fetal, preparándola para su viaje espiritual.

Acomodaron las decenas de caparazones alrededor de la cabeza, las caderas y el entorno. Luego la pertrecharon de objetos mágicos preciosos: alas de águila dorada, la pelvis de un leopardo, y el pie mutilado de un ser humano.

Ahora la pequeña cueva conocida entre los arqueólogos como Cueva Hilazon Tachtit, elegida como lugar de descanso de esta mujer es objeto de una intensa investigación encabezada por Leore Grosman, una arqueóloga de la Universidad Hebrea de Jerusalén en Israel.

La investigación ha revelado que la mujer-un misterio miembro de la cultura Natufia, que floreció entre 15.000 y 11.600 años atrás, en lo que hoy es Israel, Jordania, Líbano, Siria y, posiblemente, es una antigua chamán. Considerada una experta hechicera y curandera, fue vista probablemente como un conducto para el mundo de los espíritus, con capacidad para comunicarse con los poderes sobrenaturales en nombre de su comunidad.

http://www.lavozdelsandinismo.com/img/info/leore-grosman-2008-11-06-10464.jpg

Los humanos primitivos ya organizaban banquetes comunitarios

Un grupo internacional de científicos ha descubierto que los festines comunitarios, un comportamiento social único y común a todos los seres humanos, comenzaron antes de la llegada de la agricultura en las sociedades humanas. La prueba la han encontrado en un yacimiento funerario que data de hace unos 12.000 años.

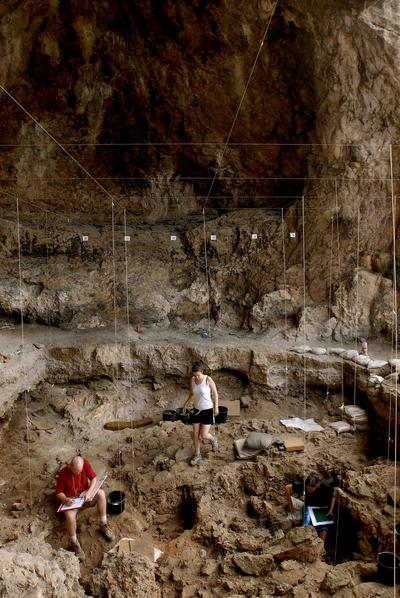

Vista del área de excavación en la Cueva Hilazon Tachtit, Israel.

“Los científicos han especulado con que este comportamiento apareció antes del período neolítico, hace cerca de 11.500 años. Esta es la primera prueba sólida que confirma la teoría de que los festines comunitarios ya tenían lugar, quizá con cierta frecuencia, en los albores de la transición hacia la agricultura”, declara Natalie Munro, investigadora de la Universidad de Connecticut (EEUU) y autora principal del estudio que se publica en el último número de la revista Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Los festines comunitarios son uno de los comportamientos sociales más universales e importantes observados en los seres humanos. El grupo de científicos que dirige Munro ha descubierto la prueba inequívoca más temprana de este tipo de festines organizados en un yacimiento funerario que data de hace unos 12.000 años.

Un festín de tortugas y reses salvajes

En una cueva sepulcral de la región de Galilea -al norte de Israel-, Munro y Leore Grosman, investigadora de la Universidad Hebrea en Jerusalén, descubrieron los restos de al menos 71 tortugas y tres reses salvajes en dos huecos excavados y con una densidad poco habitual para el período.

“Los caparazones de las tortugas y los huesos de las reses muestran pruebas de haber sido cocinados y desgarrados, lo que indica que los animales fueron descuartizados para el consumo humano”, explican los expertos.

“Por sí sola, la carne de los caparazones de tortuga desechados podría haber alimentado a 35 comensales. No sabemos exactamente cuántos individuos asistieron a este banquete en particular o cuál era la asistencia media a este tipo de eventos. Lo único que podemos hacer es dar un número mínimo estimado basándonos en los huesos que hallamos”, afirma Munro.

Según las investigadoras, cada uno de los dos huecos encontrados se excavó para celebrar un ritual funerario humano con su correspondiente banquete. Los caparazones de tortuga estaban situados debajo, alrededor y sobre los restos de un chamán que había sido enterrado mediante un rito, lo que sugiere que el banquete tuvo lugar al mismo tiempo que el ritual funerario.

Convites para fomentar las relaciones sociales

Una de las principales razones por las que los humanos comenzaron a celebrar estos festines, y después a cultivar sus propios alimentos, es que el rápido crecimiento de la población humana había empezado a abarrotar sus tierras.

“Existía mucho más contacto entre los humanos, y esto podía crear conflictos. En períodos anteriores a la Edad de Piedra, había pequeños grupos familiares que normalmente se movían para buscar nuevas fuentes de alimento. Posteriormente, estos eventos públicos eran una oportunidad de hacer ‘comunidad’ y ayudar a liberar tensiones y a consolidar las relaciones sociales”, asegura la investigadora estadounidense.

El origen de la agricultura

“La aparición de estos festines en los albores de la agricultura es particularmente interesante porque los humanos comenzaban a experimentar con la domesticación y el cultivo”, señala Munro.

“En conjunto, esta integración comunitaria y los cambios en la economía se sucediendo desde el principio, cuando el cultivo incipiente inició su desarrollo. Estos tipos de cambios sociales son el origen de los cambios significativos en la complejidad de la sociedad humana que dieron lugar a la transición a la agricultura”, concluye la investigadora. publicado en Servicio de Información y Noticias Científicas (SINC).

http://www.agenciasinc.es/esl/Noticias/Los-humanos-primitivos-ya-organizaban-banquetes-comunitarios

.

Remains of tortoises feasted on by humans as part of the burial ritual. Natalie Munro, associate professor of anthropology, photographing a grave thought to be that of a shaman at the archaeological site of Hilazon Tachtit Cave in northern Israel.

www.bloganavazquez.com/tag/hilazon-tachtit/

www.bloganavazquez.com/tag/hilazon-tachtit/

.

Community feasting dates back 12,000 years

Community feasting is one of the most universal and important social behaviours found among humans. Now, scientists have found the earliest clear evidence of organized feasting, from a burial site dated about 12,000 years ago. These remains represent the first archaeological verification that human feasting began before the advent of agriculture.

“Scientists have speculated that feasting began before the Neolithic period, which starts about 11.5 thousand years ago,” says Natalie Munro of the University of Connecticut, and author of a research article released yesterday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. “This is the first solid evidence that supports the idea that communal feasts were already occurring – perhaps with some frequency – at the beginnings of the transition to agriculture.”

At a burial cave in the Galilee region of northern Israel, Munro and her colleague Leore Grosman of Hebrew University in Jerusalem uncovered the remains of at least 71 tortoises and three wild cattle in two specifically crafted hollows, an unusually high density for the period. The tortoise shells and cattle bones exhibited evidence of being cooked and torn apart, indicating that the animals had been butchered for human consumption.

Each of the two hollows, says Munro, was manufactured for the purpose of a ritual human burial and related feasting activities. The tortoise shells were situated under, around, and on top of the remains of a ritually-buried shaman, which suggests that the feast occurred concurrently with the ritual burial. On their own, the meat from the discarded tortoise shells could probably have fed about 35 people, says Munro, but it’s possible that many more than that attended this feast.

“We don’t know exactly how many people attended this particular feast, or what the average attendance was at similar events, since we don’t know how much meat was actually available in the cave,” says Munro. “The best we can do is give a minimum estimate, based on the bones that are present.”

A major reason why humans began feasting – and later began to cultivate their own foods – is because faster human population growth had begun to crowd the landscape. In earlier periods of the Stone Age, says Munro, small family groups were often on the move to find new sources of food. But around the time of this feast, she says, that lifestyle had become much more difficult.

“People were coming into contact with each other a lot, and that can create friction,” she says. “Before, they could get up and leave when they had problems with the neighbors. Now, these public events served as community-building opportunities, which helped to relieve tensions and solidify social relationships.”

But when a once-nomadic group of humans settles down, that can put tremendous pressure on the local resources. Munro notes that humans around the time of this feast were intensively using the plants and animals that their descendants later domesticated.

“The appearance of these feasts at the beginnings of agriculture is particularly interesting because people are starting to experiment with domestication and cultivation,” she notes.

This combination of increased social interaction and changes in resources, says Munro, is what eventually led to the beginnings of agriculture.

Taken together, this community integration and the changes in economics were happening at the very beginning when incipient cultivation was getting going,” she says. “These kinds of social changes are the beginnings of significant changes in human social complexity that lead into the beginning of the agricultural transition.”

Munro, who started studying anthropology in her junior year of high school, now is the head of UConn’s zooarchaeology lab, which focuses on the study of animal remains from archaeological sites. Although much of her work focuses on the biology and ecology of these animals, she enjoys studies – like this one – that have direct implications for human culture.

“I’m more often talking about the biology of animals, but in these cases, it’s fun to think about humans and their social interactions,” she says.

In particular, she says, she never tires of excavating unusual and fascinating animal remains.

“What was really fun was being in the cave and uncovering all these unexpected animal parts – like cows’ tails, and even a leopard pelvis!” she says. “It was so exciting to excavate those with my own two hands.”

September 23, 2010

.

Packed with blackened tortoise shells, an ancient shaman's grave may be evidence of early feasting.

Packed with blackened tortoise shells, an ancient shaman's grave may be evidence of early feasting.

.

Ancient Sorcerer's "Wake" Was First Feast for the Dead?

Leftovers, skeletons hint that world's first villagers fostered peace via partying.

Heather Pringle for National Geographic magazine

Published August 30, 2010

Some 12,000 years ago in a small sunlit cave in northern Israel, mourners finished the last of the roasted tortoise meat and gathered up dozens of the blackened shells. Kneeling down beside an open grave in the cave floor, they paid their last respects to the elderly dead woman curled within, preparing her for a spiritual journey.

They tucked tortoise shells under her head and hips and arranged dozens of the shells on top and around her. Then they left her many rare and magical things—the wing of a golden eagle, the pelvis of a leopard, and the severed foot of a human being.

Now called Hilazon Tachtit, the small cave chosen as this woman's resting place is the subject of an intense investigation led by Leore Grosman, an archaeologist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel.

Already her research has revealed that the mystery woman—a member of the Natufian culture, which flourished between 15,000 and 11,600 years ago in what is now Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and possibly Syria—was the world's earliest known shaman. Considered a skilled sorcerer and healer, she was likely seen as a conduit to the spirit world, communicating with supernatural powers on behalf of her community, Grosman said.

(See "Oldest Shaman Grave Found; Includes Foot, Animal Parts.")

A study published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by Grosman and Natalie Munro, a zooarchaeologist at the University of Connecticut, reveals that the shaman's burial feast was just one chapter in the intense ritual life of the Natufians, the first known people on Earth to give up nomadic living and settle in villages.

In the years that followed the burial, many people repeatedly climbed the steep, 492-foot-high (150-meter-high) escarpment to the cave, carrying up other members of the community for burial as well as hauling large amounts of food. Next to the graves, the living dined lavishly on the meat of aurochs, the wild ancestors of cattle, during feasts conducted perhaps to memorialize the dead.

New evidence from Hilazon Tachtit, in northern Israel's Galilee region, suggests that mortuary feasting began at least 12,000 years ago, near the end of the Paleolithic era. These events set the stage for later and much more elaborate ceremonies to commemorate the dead among Neolithic farming communities.

In Britain, for example, Neolithic farmers slaughtered succulent young pigs 5,100 years ago at the site of Durrington Walls, near Stonehenge, for an annual midwinter feast. As part of the celebrations, participants are thought to have cast the ashes of compatriots who had died during the previous year into the nearby River Avon.

(See "Stonehenge Was Cemetery First and Foremost, Study Says.")

The Natufian findings give us our first clear look at the shadowy beginnings of such feasts, said Ofer Bar-Yosef, an archaeologist at Harvard University.

"The Natufians," Bar-Yosef said, "were like the founding fathers, and in this sense Hilazon Tachtit gives us some of the other roots of Neolithic society."

Study co-author Grosman agrees. "The Natufians," she said, "had one leg in the Paleolithic and one leg in the Neolithic."

Prehistoric Feast Focused on Disabled Shaman

Perched high above the Hilazon River in western Galilee, Hilazon Tachtit cave was long known only to local goatherds and their families. But in the early 1990s Harvard's Bar-Yosef spotted several Natufian flint artifacts scattered along the arid, shrubby slope below the cave and climbed up to investigate.

Impressed by the site's potential, the Harvard University archaeologist recruited Hebrew University's Grosman to take charge of the dig, and she and a small team began excavations there in 1995.

First Grosman and her team had to peel back an upper layer of goat dung, ash, and pottery sherds that had accumulated over the past 1,700 years. Below this layer they found five ancient pits filled with bones, distinctive Natufian stone tools, and pieces of charcoal that dated the pits to between 12,400 and 12,000 years ago.

At the bottom of one pit lay the 45-year-old shaman—quite elderly for Natufian times—buried with at least 70 tortoise shells [NM2] and parts of several rare animals.

Analyses showed that this woman had suffered from a deformed pelvis. She would have had a strikingly asymmetrical appearance and likely limped, dragging her foot.

Grosman examined historical accounts of shamans worldwide and found that in many cultures shamans often possessed physical handicaps or had suffered from some form of trauma.

According to Brian Hayden, an archaeologist at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, Canada, "It's not uncommon that people with disabilities, either mental or physical, are thought to have unusual supernatural powers."

Natufians Opened Graves for Display?

After burying their spiritual leader 12,000 years ago at Hilazon Tachtit, Natufians returned to the cave for other funerary rituals, eventually interring the bodies of at

least 27 men, women, and children in three communal burial pits, researchers say.

On some later visits, Natufians opened the communal graves and removed certain bones, including skulls, for possible display or burial elsewhere, according to Grosman.

Until now, removing bones from burials for use in rituals was thought to have begun during the Neolithic era at sites such as the West Bank's Jericho, dating to about 11,000 years ago. A similar practice has been found at the later Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük in Turkey.

In both places mourners coated human heads with plaster and kept them for ceremonial purposes. (Related: "Ancient Human-Bone Sculptors Turned Relatives Into Tools.")

Prehistoric Cattle Ritually Devoured at Feast

"We think that there were scheduled visits to Hilazon Tachtit," said study co-author Grosman, who received partial funding from the National Geographic Society's Committee for Research and Exploration for her work at the Natufian site. (The National Geographic Society owns National Geographic News.)

Natufians seem to have made the steep climb laden with joints of mountain gazelle and aurochs. In what might have been one sitting, the mourners devoured an estimated 661 pounds (300 kilograms)[NM3] of aurochs [NM4] meat, according to the study.

But they did not bring all this food for a picnic. In their daily lives Natufian families seldom dined on aurochs, for the wild oxen were relatively scarce at this time. And given the species' power and speed, hunting an aurochs likely required a communal effort.

The celebrants chose to feast on aurochs for reasons above and beyond their nutritional value.

"In later times we know that the aurochs become ritually important in the area," zooarchaeologist Natalie Munro said. Indeed, some later cultures seem to have regarded aurochs as sacred animals, even symbols of fertility.

For example, at the massive, 11,600-year-old Gobekli Tepe ritual site in Turkey—seen by some as the world's oldest temple—hunters and gatherers dined lavishly on aurochs.

Good Feasts Make Good Neighbors

Munro thinks that the grand ritual feasts at Hilazon Tachtit served an important purpose besides mourning lost loved ones.

Living for the first time in settled communities, Natufian families had to find a way to ease all the friction that would build up from continually rubbing shoulders with their neighbors, she says. Unlike other Paleolithic hunters and gathers, the Natufians could no longer split up and move on easily when trouble arose. They had become so populous that they could no longer find unoccupied territory in their region.

The Natufians devised another way of dealing with the strain—throwing big communal parties to celebrate important ritual events, the researchers say. "When people feel like they are part of the same group, they are more willing to share and to compromise to resolve conflict," Munro said.

The new finds suggest that the deep roots of communal feasting and the curation of human remains for ritual—found later at sites like Gobekli Tepe, Jericho, and Stonehenge—originated centuries before the advent of agricultural societies.

These rituals played an important role in smoothing the transition of Paleolithic hunter-gatherers to a farming life, researchers say. (Related: "Egypt's Earliest Farming Village Found.")

"Hilazon Tachtit," archaeologist Ofer Bar-Yosef said, "gives us a good window into these kinds of special activities. And I think that's really important."

at Hilazon Tachtit Cave

448 × 480 - 112 k - jpg

archaeologynewsnetwork...