Primera mujer condenada por genocidio es de Ruanda y ... oh!!! ironía ... era Ministra de la Mujer y la Familia

Some 800,000 people, essentially Tutsis, were killed in the genocide.

La condenada carga 800.000 muertos que fueron asesinados en 1994.

Las milicias de la etnia hutu, que la condenada contribuyó a crear desde el Gobierno, debían impedir nacimientos dentro de la etnia tutsi para así LOGRAR SU EXTERMINIO...

.

.

Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, de la etnia mayoritaria hutu, de 65 años y antigua ministra ruandesa de la Mujer y la Familia, ha sido condenada a cadena perpetua.

La ex Ministra de la Mujer y la Familia organizó el secuestro y violación de mujeres y niñas tutsi, la comunidad minoritaria. Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, fue ayudada por su hijo, Arsene Shalom Ntahobaki, pertenecientes a la etnia mayoritaria hutu, que recibe la misma pena, también ordenó el asesinato de civiles tutsi en su ciudad, Butare, al sur de Ruanda. En 1994, el intento de "exterminio de la población tutsi por parte del Gobierno hutu, dejó al menos 800.000 muertos.

-------------------------------

El Tribunal Penal Internacional para Ruanda condena a la primera mujer por genocidio

.

La ex ministra de la Familia, Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, y su hijo, de etnia hutu, alentaron la matanza de civiles tutsis en el país africano

.

ISABEL FERRER | La Haya 24/06/2011

El Tribunal Penal Internacional para Ruanda (TPIR), con sede en Arusha (Tanzania), ha dictado la primera sentencia por genocidio contra una mujer. Se trata de Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, de 65 años y antigua ministra ruandesa de la Mujer y la Familia, que ha sido condenada a cadena perpetua. La procesada es de etnia hutu, mayoritaria en el país africano, y los jueces han fallado que organizó el secuestro y violación de mujeres y niñas tutsi, la comunidad minoritaria. Ayudada por su hijo, Arsene Shalom Ntahobaki, que recibe la misma pena, también ordenó el asesinato de civiles tutsi en su ciudad, Butare, al sur de Ruanda. En 1994, el intento de "exterminio de la población tutsi por parte del Gobierno hutu, dejó al menos 800.000 muertos. Naciones Unidas calcula que ello supone el 11% del total de la población. La tragedia se desató ante la pasividad de la comunidad internacional, más preocupada por mantener su influencia en África que por evitarla.

Según el TPIR, las milicias hutu, que la procesada contribuyó a crear desde el Gobierno, debían impedir nacimientos dentro del grupo tutsi. En un país donde la pertenencia a una etnia está ligada al linaje paterno, forzar a una mujer y dejarla embarazada equivale a destruir a la comunidad atacada. Las supervivientes de las masacres y violaciones recordaron ante los jueces momentos dantescos. Cuando las que eran ya madres pedían clemencia, "eran degolladas sin miramientos", rezan sus testimonios. Otro pasaje cita la respuesta dada por los milicianos que salían a violar: "Lo hacemos en nombre de Nyiramasuhuko. Es nuestro premio por poner en su lugar a las mujeres (tutsi) que nos miran con desprecio", decían.

También se ha recogido en el juicio un episodio sobre la presencia de la acusada en un puesto de la Cruz Roja y la catástrofe posterior. Se trataba de repartir comida, y los refugiados tutsi acudieron a cientos. Una vez allí, los hombres fueron separados de las mujeres. Ellos perecieron ametrallados. Ellas fueron violadas antes de morir. La fiscalía de Tribunal subrayó el hecho de que la procesada y su hijo, "forzaran a sus víctimas a desnudarse antes de meterlos en camiones para darles muerte". La ex ministra huyó a Congo tras el genocidio y trabajó como asistente social con los refugiados. En 1997 fue arrestada en Kenia. Siempre ha negado los hechos.

El caso de Nyiramasuhuko ilustra dos aspectos señalados de la justicia internacional. Por un lado, confirma que la violación constituye genocidio cuando se utiliza como método de tortura generalizada. De otro, muestra la lentitud de algunos procesos que han dividió a comunidades enteras. El juicio de la ex ministra africana ha tardado 10 años en cerrarse y ello lastra las posibilidades de una reconciliación nacional. Además, como en el caso del Tribunal Penal para la antigua Yugoslavia (TPIY), con sede en La Haya, el de Ruanda tiene varios prófugos. Uno de los más notorios es Felicien Kabuga, un empresario que habría financiado el genocidio. Estados Unidos cree que se oculta en Kenia.

Kivu revive los fantasmas de Ruanda

Paul Kagame se eterniza en Ruanda

Uganda detiene al arquitecto del genocidio de Ruanda

El precio de mirar hacia otro lado

El gobierno francés, bajo sospecha por el genocidio de Ruanda

Condenado a cadena perpetua el líder del genocidio en Ruanda

Una mujer consuela a otra durante la ceremonia del 15 aniversario del genocidio en Ruanda

-Some 800,000 people, essentially Tutsis, were killed in the genocide

http://img2.allvoices.com/thumbs/event/900/570/63449164-some-.jpg

http://img2.allvoices.com/thumbs/event/900/570/63449164-some-.jpg

-

Publicado el 24/06/2011 por euronewses

------------------------------------------------

Primera mujer condenada por genocidio en Ruanda. Fotos de 10 años de barbarie

Un trabajador limpia una fosa común, con varias víctimas del genocidio, en una iglesia de Nyanza.

Un crucifijo y un rosario fueron colocados junto a las calaveras de algunas víctimas del genocidio, en una iglesia católica de Ntarama.

Una niña ruandesa camina por el cementerio de Nyaza, en esta imagen del 25 de noviembre de 1996.

Una mujer desnutrida toma leche en una clínica de rehabilitación en Ruhango, al suroeste de Kigali. La foto fue tomada el 6 de junio de 1994.

Ruandeses cargan con baldes de agua, que tratan de transportar al campo de refugiados de Benaco, en Tanzania, en esta imagen del 17 de mayo de 1994.

Unos niños imploran a los soldados zaireños que les sea permitido cruzar el puente que separa Ruanda de Zaire, para así seguir a sus madres. La foto es del 20 de agosto de 1994.

http://media.terra.es/galerias/294/9221.html

El Tribunal Penal Internacional para Ruanda condena a la primera mujer por genocidio

La ex ministra de la Familia, Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, y su hijo, de etnia hutu, alentaron la matanza de civiles tutsis en el país africano

ISABEL FERRER | La Haya 24/06/2011

Cadáveres de las víctimas de los enfrentamientos tribales de Ruanda, amontonados en las calles de su capital, Kigali (1994).-

------------------------------------------

The Feminine Mystique

The Feminine Mystique

There's a certain strain of feminism distinguished by its rejection of the notion that women are merely equals of men. I've always considered this to be utter nonsense.

There's a certain strain of feminism distinguished by its rejection of the notion that women are merely equals of men. I've always considered this to be utter nonsense.

There's a certain strain of feminism distinguished by its rejection of the notion that women are merely equals of men. If only women ran the world, its disciples sigh, there would be no war, no violence, no rape, no oppression, no assorted other bad stuff. I've always considered this to be utter nonsense. True, the worst monsters of history have all been male, but women have historically lacked access to the sort of power required to order mass slaughter. Women's better record is more a matter of opportunity than motivation.

Those who disagree may wish to read about Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, the former Rwandan minister of family and women's affairs, and the first woman to go on trial for genocide.

Pauline once traveled the countryside lecturing on female empowerment, child care, and AIDS prevention. In the spring of 1994, she returned to her home town of Butare, where, clad in military fatigues and toting a machine gun, she presided over the massacre of thousands of people from the Tutsi ethnic group. She was hardly alone, as during this period approximately 800,000 Tutsi were killed in the Hutu-led government's gruesome policy of ethnic cleansing. As the article describes, the Hutu militias did not simply kill, but also raped at least a quarter million women, as a deliberate tactic of demoralization. Many of the women were then killed, after being subjected to horrific mutilation.

Pauline once traveled the countryside lecturing on female empowerment, child care, and AIDS prevention. In the spring of 1994, she returned to her home town of Butare, where, clad in military fatigues and toting a machine gun, she presided over the massacre of thousands of people from the Tutsi ethnic group. She was hardly alone, as during this period approximately 800,000 Tutsi were killed in the Hutu-led government's gruesome policy of ethnic cleansing. As the article describes, the Hutu militias did not simply kill, but also raped at least a quarter million women, as a deliberate tactic of demoralization. Many of the women were then killed, after being subjected to horrific mutilation.

One might imagine that Pauline, even if she endorsed her government's policy of ethnic elimination would, as a woman, have done her best to restrain her followers from rape. One would be wrong.

According to witnesses, Pauline instead goaded her followers, commanding, "Before you kill the women, you need to rape them." In another incident, she ordered her men to take cans of gasoline from her car and use it to burn a group of women to death. A surviving rape victim who had been left alive as a witness to Hutu "progress" testified that she had seen numerous atrocities, including rape, mutilation, and murders of women. All the while, she testified, she heard the soldiers say, "We are doing what was ordered by Pauline Nyiramasuhuko."

How could Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, a woman and a mother, have done such things? The article cannot really answer such a question. Judging from the interviews with her family and aquaintances, she was an extremely ambitious person, concerned mainly with her own advancement, and it is not clear whether she was motivated by genuine animosity towards Tutsis, or by sheer opportunism. Bizarrely, she herself could have been classified as a Tutsi, reminiscent of Nazi leaders who themselves had Jewish ancestry. In the end, her case says nothing about women's nature, but offers a sadly familiar glimpse into the worst of human nature.

Posted: Sun - April 20, 2003 at 01:16 PM // Detritus Ex Machina // Women & Feminism //

homepage.mac.com/.../E1034689334/index.html

-----------------------------

God Sleeps in Rwanda

12 January, 2007 powervoyeur.blogspot.com/2007/01/god-sleeps-i...

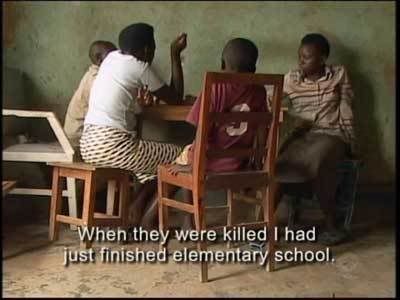

God Sleeps in Rwanda is the second documentary I've seen in this still nascent year about the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide with Rwanda: A Killer's Homecoming being the first.

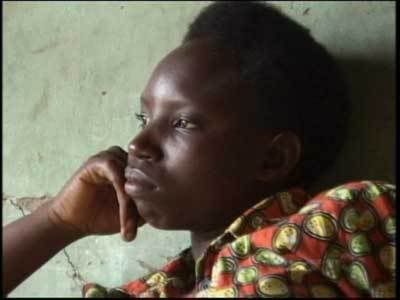

Rwanda must be an absolutely gorgeous country. I say this because of the opening shot of God Sleeps in Rwanda which is an aerial view of the countryside. It is stunning. The view then shifts down into a town and then to a road showing several women dressed in brightly-colored clothes walking towards the camera with urns atop their heads. We then meet the first of five women to be profiled, Severa Mukakinani.

Severa has a 9 year old daughter, Akimana. Over a shot of them sorting beans, we hear Severa say that she wished Akimana had died like her other seven children.

A brief overview of the genocide follows and I learned that the genocide left the Rwandan population with 70% of it being women. Narrator Rosario Dawson notes that this was a great burden for the women of Rwanda but also an extraordinary opportunity. The focus then shifts back to Severa as she explains how she lost her entire family in the genocide. She watched as her husband and three sons were killed before her. Severa also tells how she was gang raped by more men than she could count which led to her becoming pregnant with Akimana.

While she wanted to abort the pregnancy at first, Severa found that she just couldn't go through with it. She had seen the death of too many innocents already and so she decided to keep the child.

Rape was a tool used in the genocide and it is estimated that a quarter of a million women were raped during that time. As a tool of war, it was coordinated by Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, the country's Minister of Women and Family Affairs at the time.

Nyiramasuhuko is standing trial for war crimes and is the first women to be charged with genocide. It is also the first time that anyone is charged with rape as a crime against humanity.

We are then introduced to another survivor and rape victim, Chantal Kantarama.

While Chantal was lucky to have escaped the ordeal without having contracted AIDS, her friend, Fifi Mukangoga, who was also raped, was not so lucky. She talks about her close friendship with Fifi and how they fled the genocide together.

After it was over, Chantel met the man who would be her husband. They now have three children. While Fifi died of AIDS, Chantel was able to build a new life.

As with Severa, Chantal found hope and meaning in her children.

Odette Mukakabera survived the genocide along with her husband and four children. But she found out afterwards that her husband was HIV+ and had infected her. He died in 1999. A former school teacher, Odette became an officer in the Rwanda's National Police Force.

Prior to the genocide, a women in such a position was unthinkable. Also unthinkable was Odette's decision to go public with the fact that she has AIDS. This is apparently taboo in most of Africa. Unfortunately, one of Chantel's children also contracted AIDS but she is unable to afford any medication for him. In addition to being a police officer, she is also a law student and hopes to one day be a lawyer so she can help those also infected with the disease.

Next we meet a pensive Delphine Umutesi. She lost her mother at the age of 10 and watched as her father was butchered. Being the eldest of five children, Delphine was forced to assume the role of mother to her siblings at the tender age of 12. She benefited from new laws in Rwanda including one which allowed women to inherit property and their own children.

Delphine tells of the old attitudes in Rwanda towards women which was that they should remain in the home while the husband supported the family. But the genocide changed that and forced women to do everything themselves. Although she obviously has more than enough responsibility with taking care of her brothers and sisters, Delphine dreams of getting married and having children of her own. She says that several men have proposed to her, which makes me wonder exactly what the cultural norms are in Rwanda for proposing.

The last woman to be profiled was Joseline Mujawamariya. She is her town's top development official with has six underlings. We see her and several others building a road from her village to Rwanda's capital, Kigali. Joseline's position in her village is quite an accomplishment considering her lack of formal education but, given the circumstances, anything was possible. But it was her own drive to do well and contribute to her community that put her where she is. Joseline speaks of men and women working together and of shedding the old ways which disallowed women from participating in the political process.

God Sleeps in Rwanda was quite a breath of fresh air when I watched it. The documentary provided some positive glimpses of Rwanda and offered hope. For these reasons it was an official selection of the United Nations Association Film Festival's "Statement of Courage and Hope". It was an official selection at many other film festivals as well and was nominated for an Academy Award in 2005.

God Sleeps in Rwanda was quite a breath of fresh air when I watched it. The documentary provided some positive glimpses of Rwanda and offered hope. For these reasons it was an official selection of the United Nations Association Film Festival's "Statement of Courage and Hope". It was an official selection at many other film festivals as well and was nominated for an Academy Award in 2005.

As I mentioned above, there were changes in the inheritance laws and it seems these were instituted shortly after we left Odette and Theophile in Rwanda: A Killer's Homecoming. The changes should be no surprise considering the disproportionate number of women in the population. What a shame that it took a genocide for women to be able to gain these rights and for them to assume positions of authority as they are now.

One thing I noticed was how important children were to the women in the video. They survived a genocide and, in some instances, rape as well yet they were not left cold and heartless. These women still looked towards a brighter future while at the same time dealing with the past. Not only does their compassion show through but this emphasis on children also shows how a caring/nurturing side can co-exist with a side that is more about authority and leaderships. By this I mean that, here in America, we have this notion that women in positions of authority eschew a family life to pursue their career, that the two cannot co-exist. Yet here they seem to. Different societies, to be sure, but perhaps the notion is purely American.

Since the video is a short, only a few minutes could be devoted to profiling each woman. Yet I thought the filmmakers did a great job of presenting the women in a complex way. The women were given the chance to give a brief history of their lives, to explain what their lives are like now, and to talk about the changes in Rwandan society as well. One thing that was noticeably absent from the video was religion. I expected one of the women to talk about having been granted strength from God or something similar but that never happened. I have no clue as to their religious affiliations or lack thereof and the omission of religion here could very have been the prerogative of the filmmakers. Perhaps they wanted to emphasize the strength and accomplishments of their subjects without distraction.

Religious or not, these are some truly remarkable women.

ACADEMY AWARDR NOMINEE for Best Documentary Short 2005!

powervoyeur.blogspot.com/2007/01/god-sleeps-i...

Pigmeos arrinconados al borde de la extinción por ... - malcolmallison

14 Abr 2011 – Como parte de una velada campaña de exterminio digitada por el gobierno de Ruanda unos 30000 techos de paja han sido destruidos en los ...

malcolmallison.lamula.pe/...ruanda/malcolmallison - En caché

India traza su propia vía internacional sin ... - malcolmallison

16 Abr 2011 – malcolmallison. Just another Lamula.pe weblog ... El genocidio en Rwanda se ignoró durante mucho tiempo, porque es un país africano pobre, ...

malcolmallison.lamula.pe/2011/.../malcolmallison - En caché